Coffee Processing

Processing is a fascinating part of coffee growing, and how it’s done has a huge impact on the taste of the final cup. Let’s explore!

An introduction to Coffee processing

Coffee is the seed of a fruit, so to get it from the branch to your cup some processing needs to occur. This can take many forms, but at its most basic it is the act of stripping away the outer layers of fruit and drying the beans to just the right point so that they store, transport, and reach us in ideal condition ready for roasting. Processed green coffee contains between 7-12% water by weight, depending on the method used.

The two main processing methods are Natural and Washed, and there’s also a sort of cross between the two that goes by many names including Honey Process, Pulped Natural, and Semi-washed. Then there are several country-specific processes that producers have developed to cope with their location’s specific environment, like Indonesia’s Giling Basah or Wet-Hulled process.

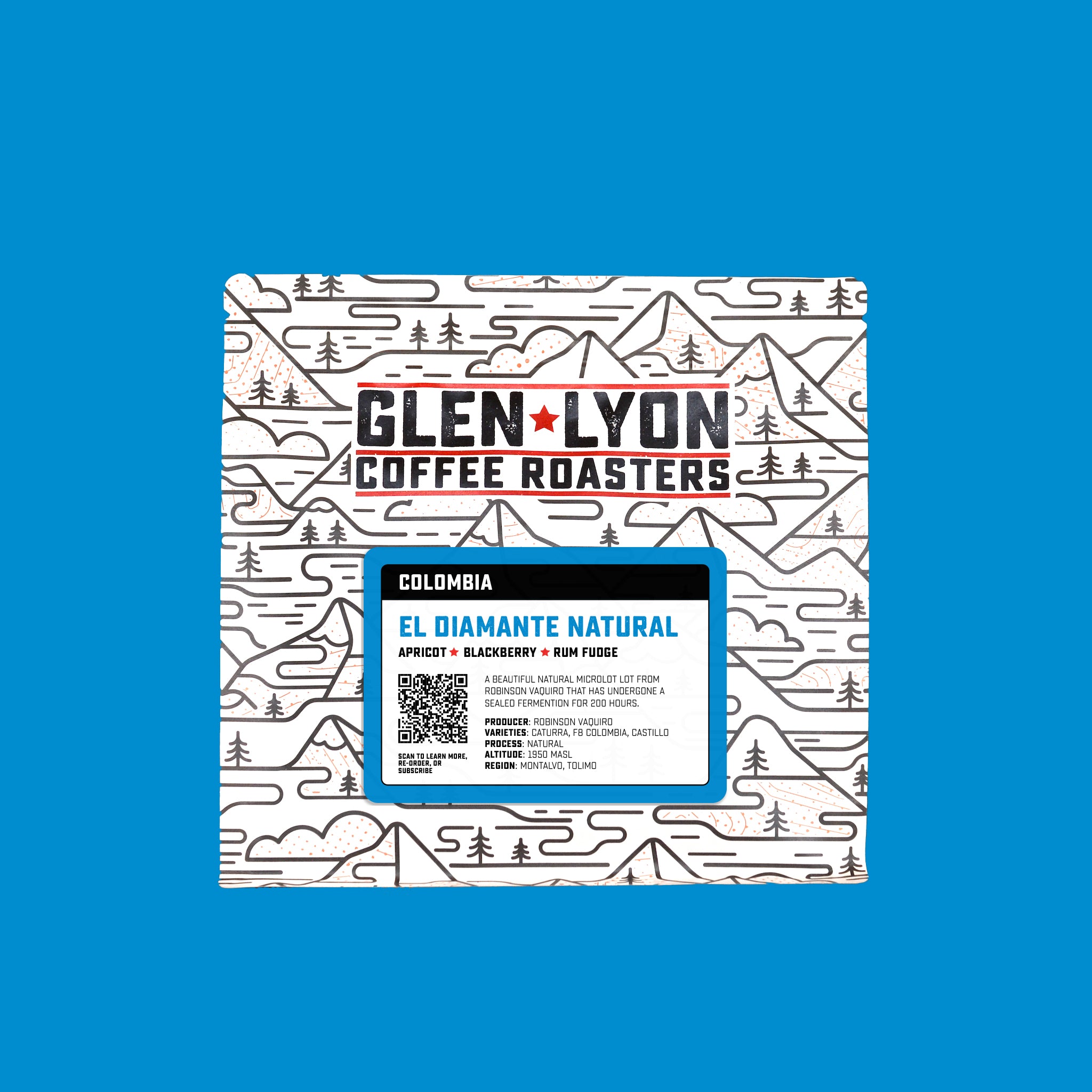

The last two decades has also seen an increase in the number of producers experimenting with new and exciting methods to augment and enhance their coffee—some have added yeast at specific points in the process, others have sealed the beans in oxygen-free chambers to intensify the fermentation.

Anatomy of a bean

Before we look at the different ways to process a coffee cherry into a green bean, let’s zoom in and take a look at its many layers.

Much like a regular cherry, a freshly-picked coffee cherry has an outer skin (the exocarp) underneath which is a fruity layer called the pulp or mucilage (mesocarp). Unlike a regular cherry, beneath that is a thin papery hull called the parchment (endocarp) and an even thinner layer called the silverskin which surrounds and protects the bean. The majority of cherries contain two seeds facing each other although occasionally, in something like five percent of cases, a natural mutation occurs which results in a single bean, or a peaberry. These are often collected and sold at a premium as a specific peaberry lot, and some people swear that peaberries make a tastier coffee.

However many beans there are, the layers surrounding it have to come off at some point before you can grind and drink your morning coffee. Choosing the way, and order, in which they are removed is where the different processing methods come in.

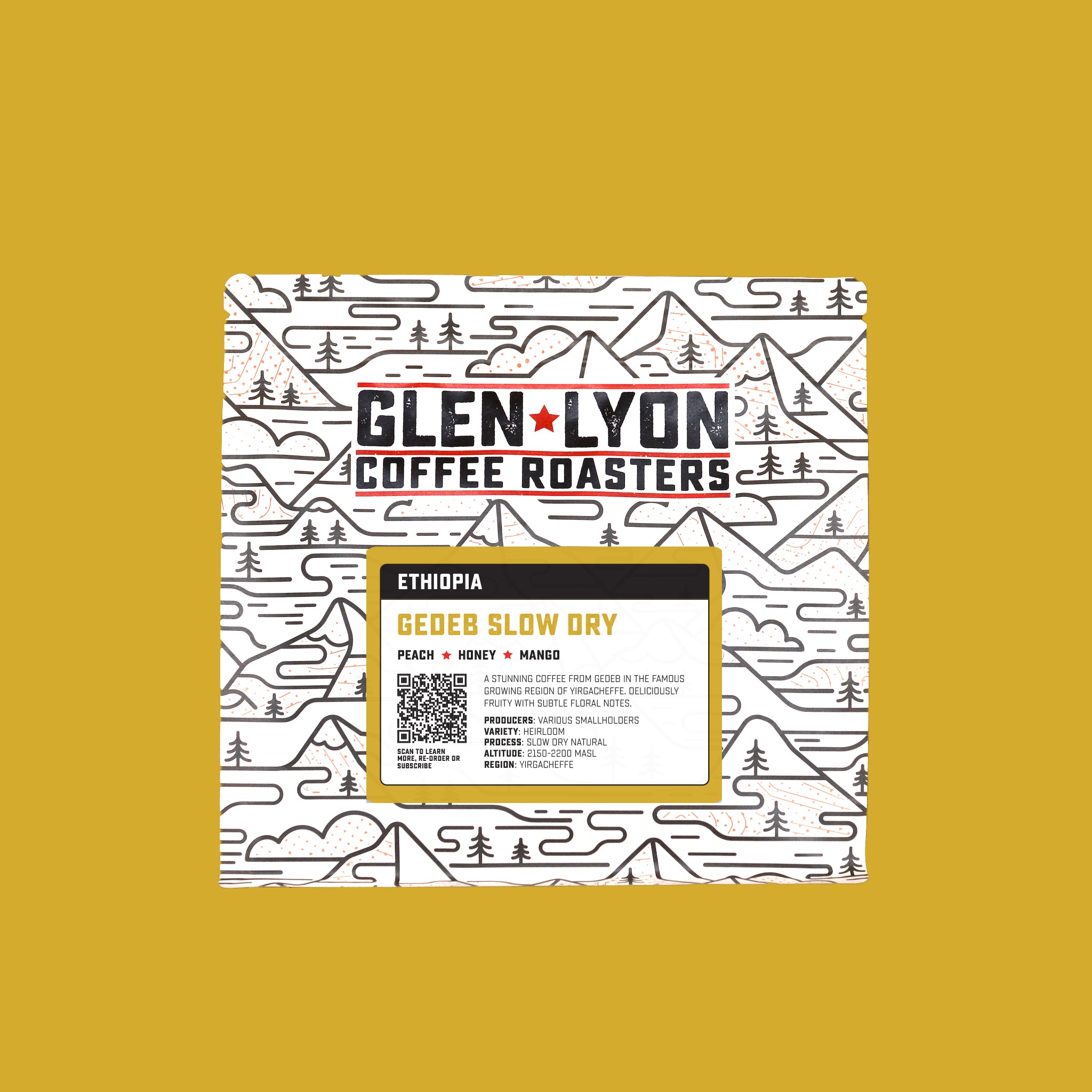

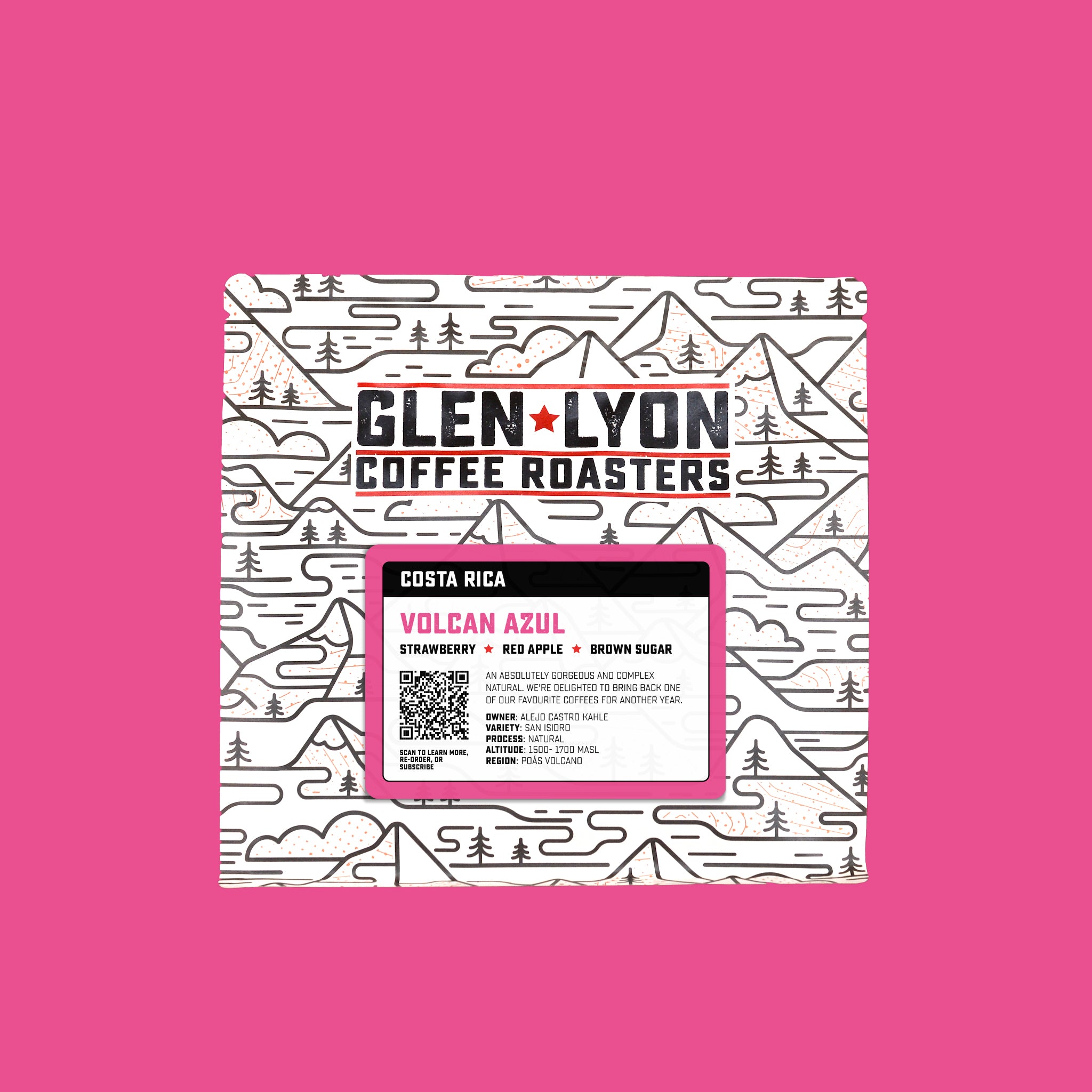

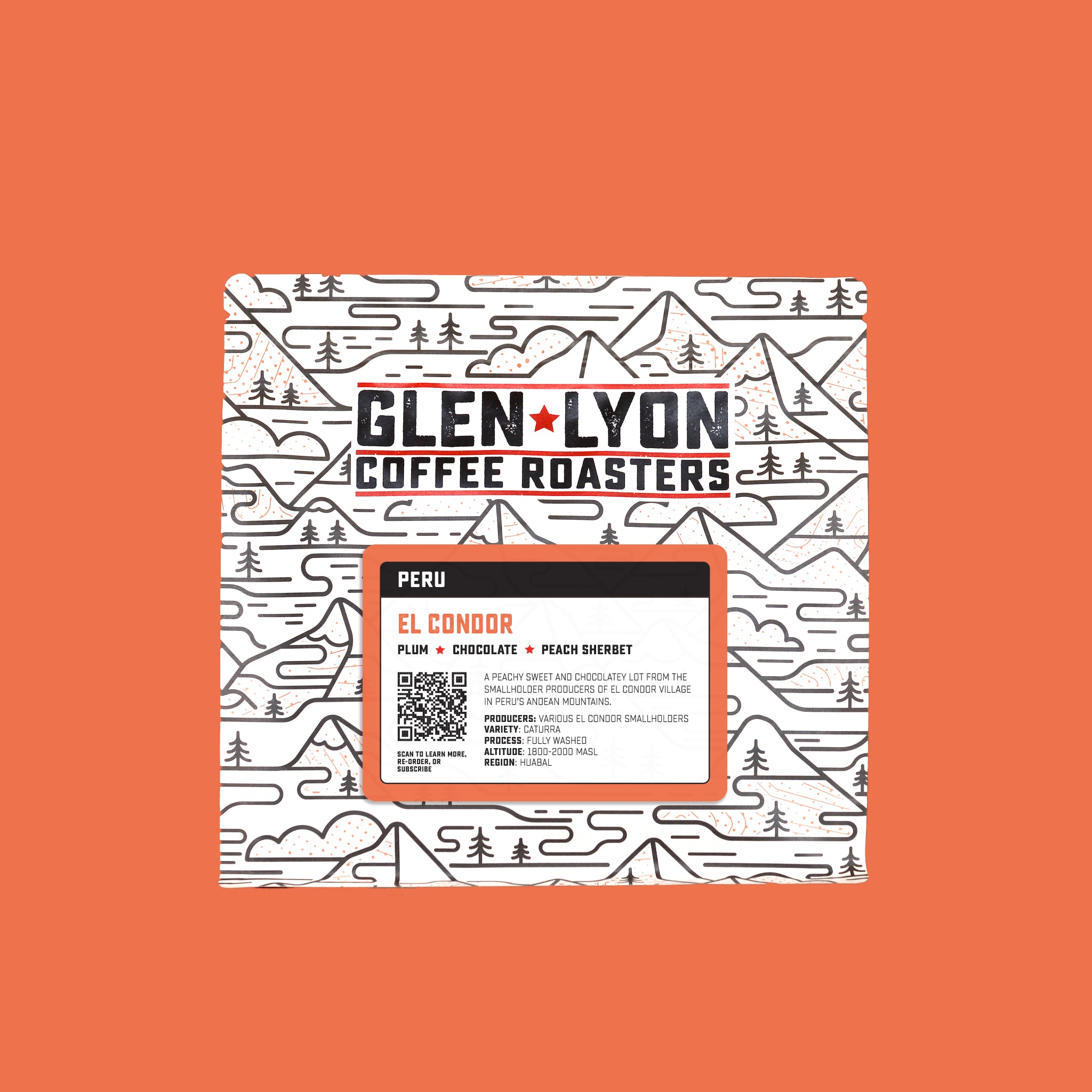

Natural process

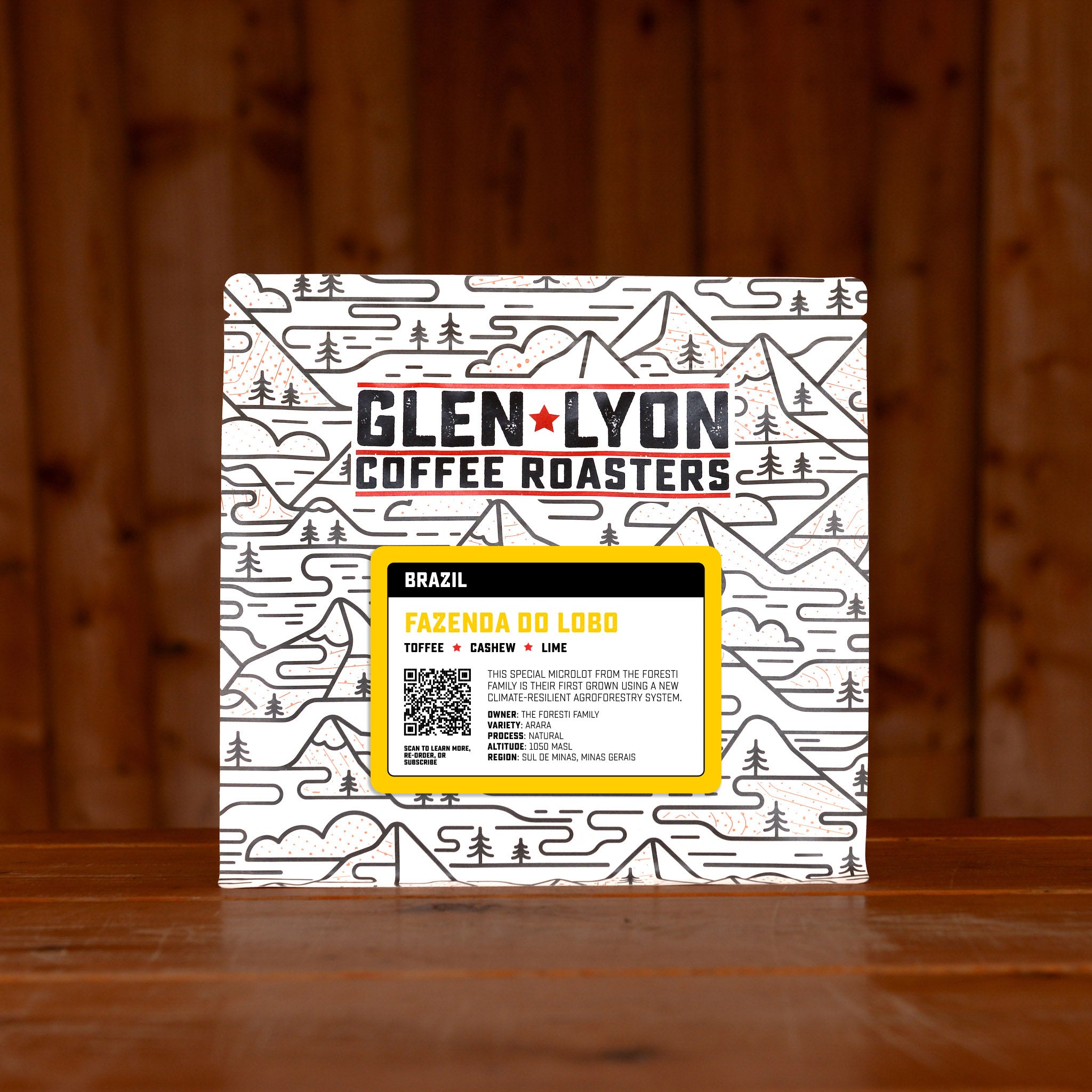

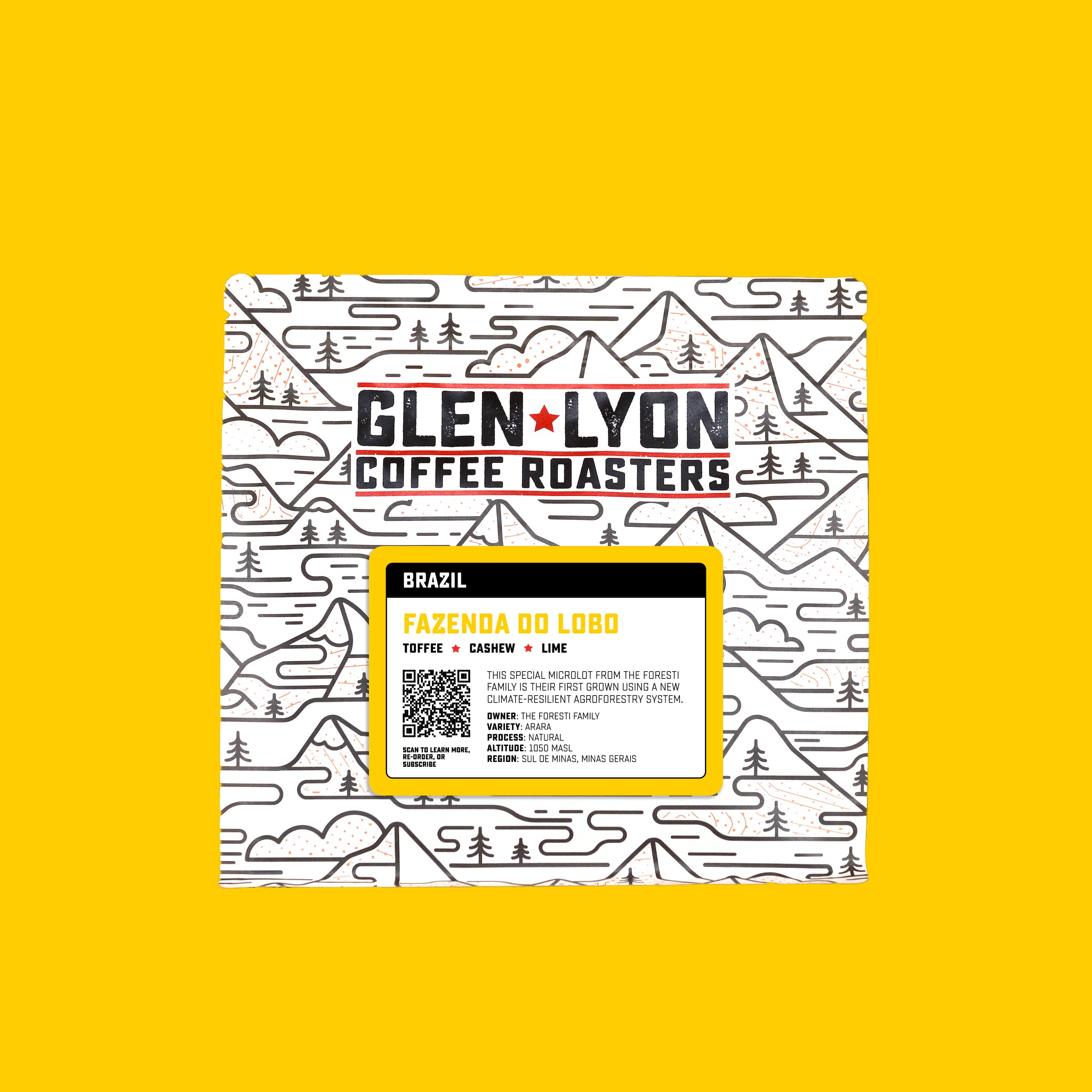

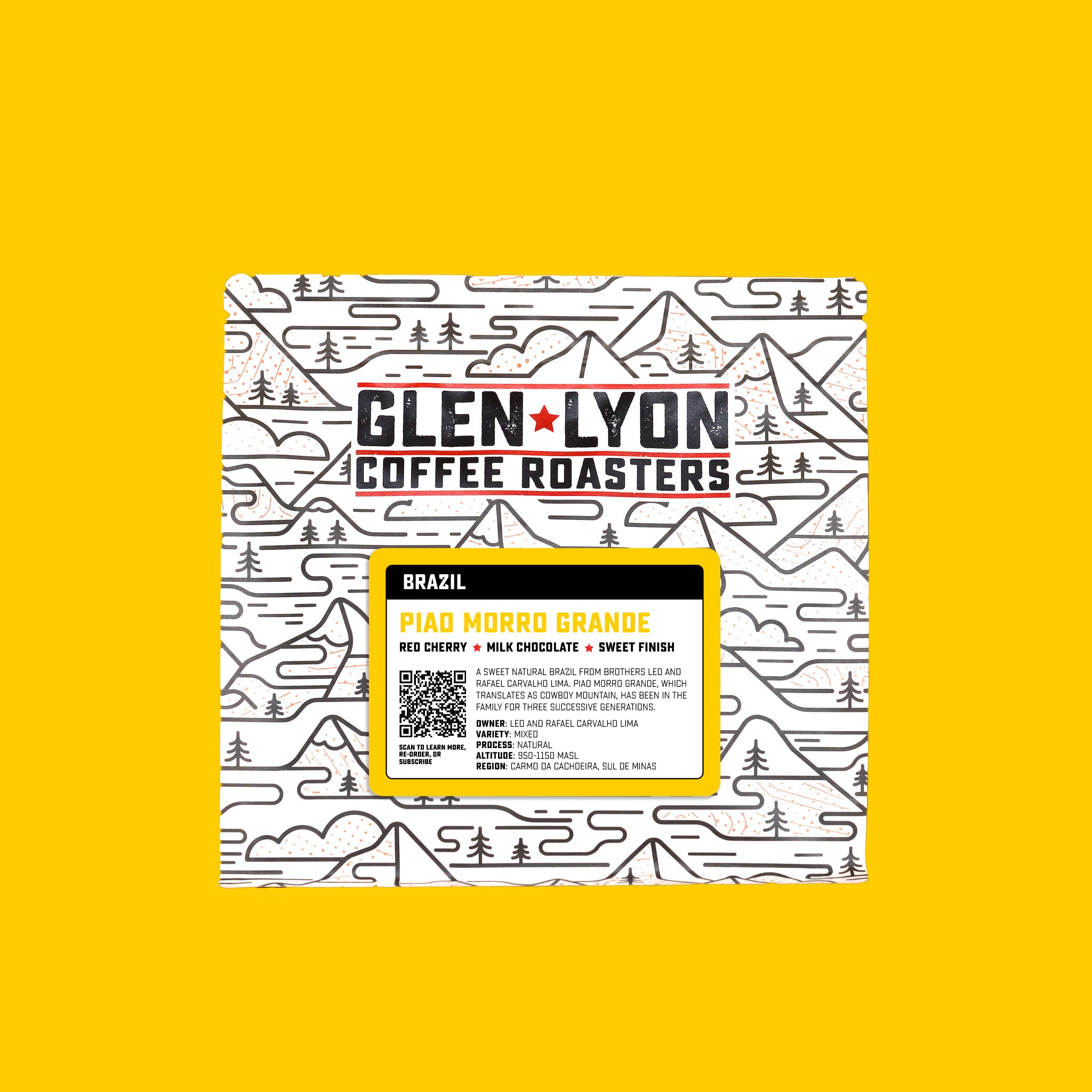

The original coffee processing method. Farmers have been using the natural (or dry) process for hundreds of years and it is also the simplest method, requiring little machinery—just labour. It is mostly, although not exclusively, used in countries with extended dry seasons such as Brazil, Ethiopia, Yemen, and Costa Rica.

In the natural process, workers pick ripe cherries, sort them to remove any foreign matter or unripe beans, and wash them before laying them in the sun to dry. Depending on the farm, this usually takes place on a patio or a raised bed or table. It can take several weeks for the cherries to dry to the desired moisture content, and during this time they must be constantly raked and turned to guard against spoilage.

During this time the cherries will begin to ferment, which allows the beans to draw in some of the flavours from the fruit. This is why natural-processed coffees tend to feature rich, fruity tasting notes, but unless closely monitored those flavours can deviate towards overfermented and musty. The drying stage is critical, as too-dry cherries can become brittle and cause broken beans while if they’re left overly moist they can attract fungi or bacteria.

Once the beans reach the desired moisture content they are ready for further processing, which involves removing the outer layers using a hulling machine at a dry mill. They are then sorted, graded, and bagged ready for export.

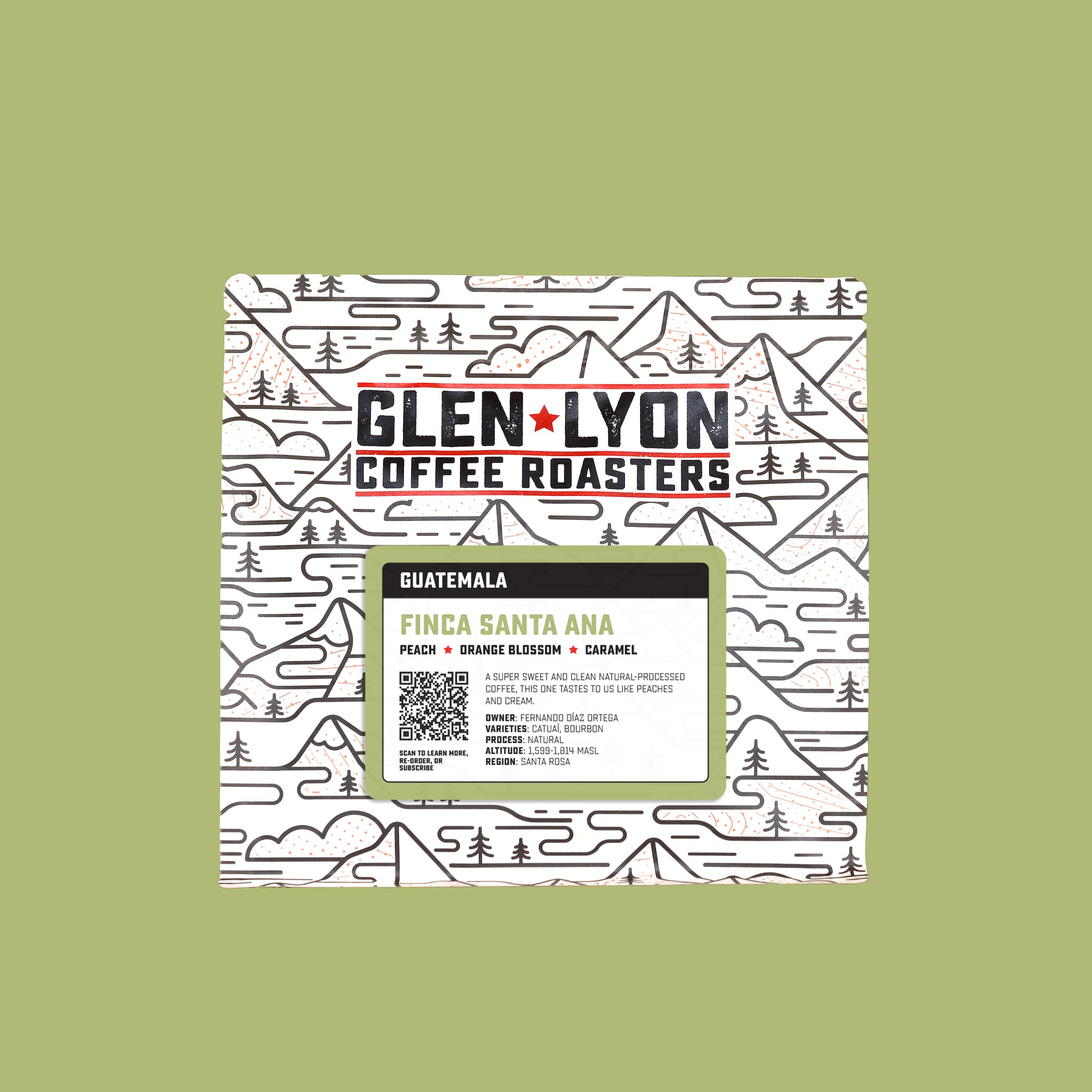

For years natural-processed coffees were considered inferior due to the possibility of off flavours developing during drying; many commercial-grade growers use this method due to its affordability. However, over the past few decades skilled producers have refined and perfected the process and today you can find incredible, complex natural-processed coffees from many countries.

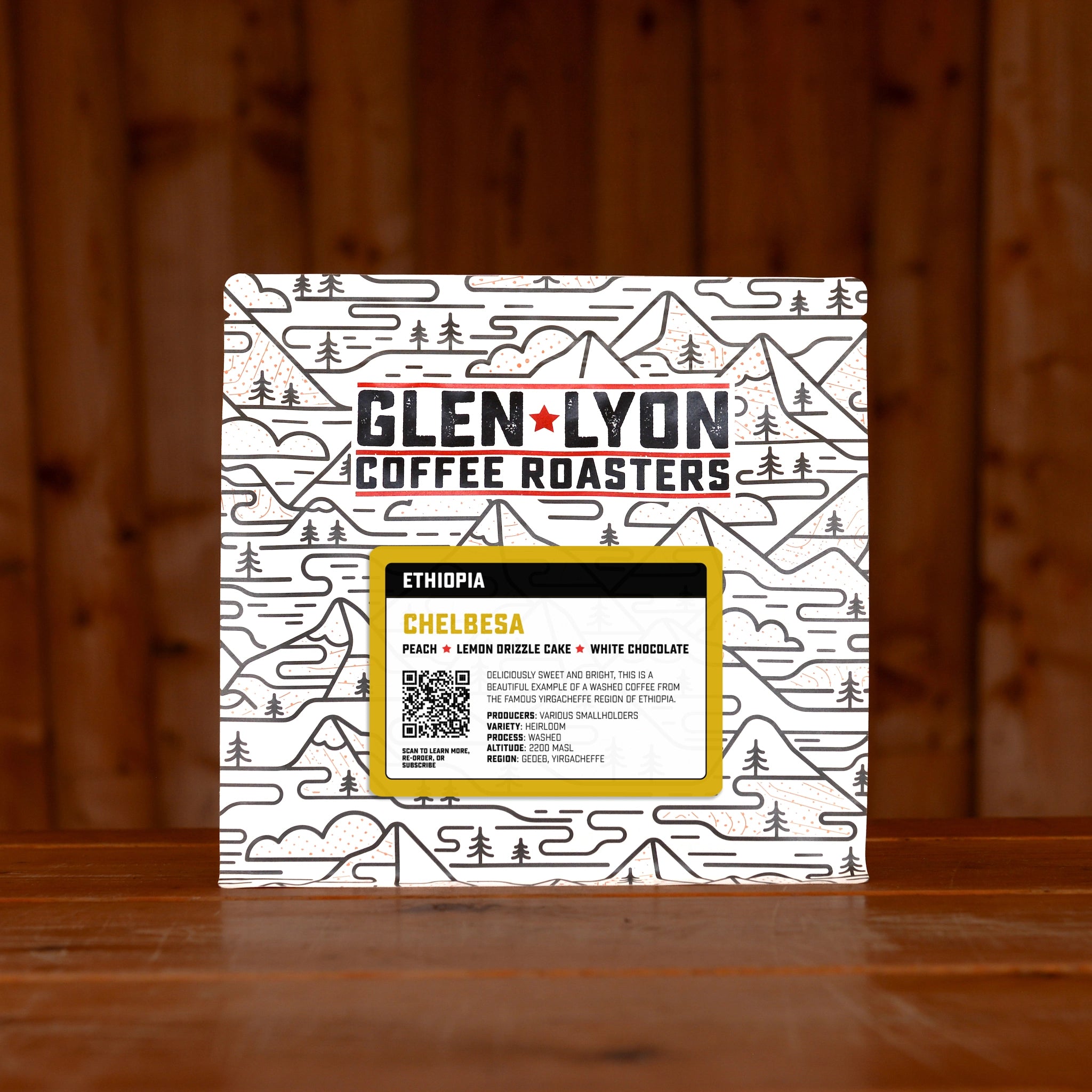

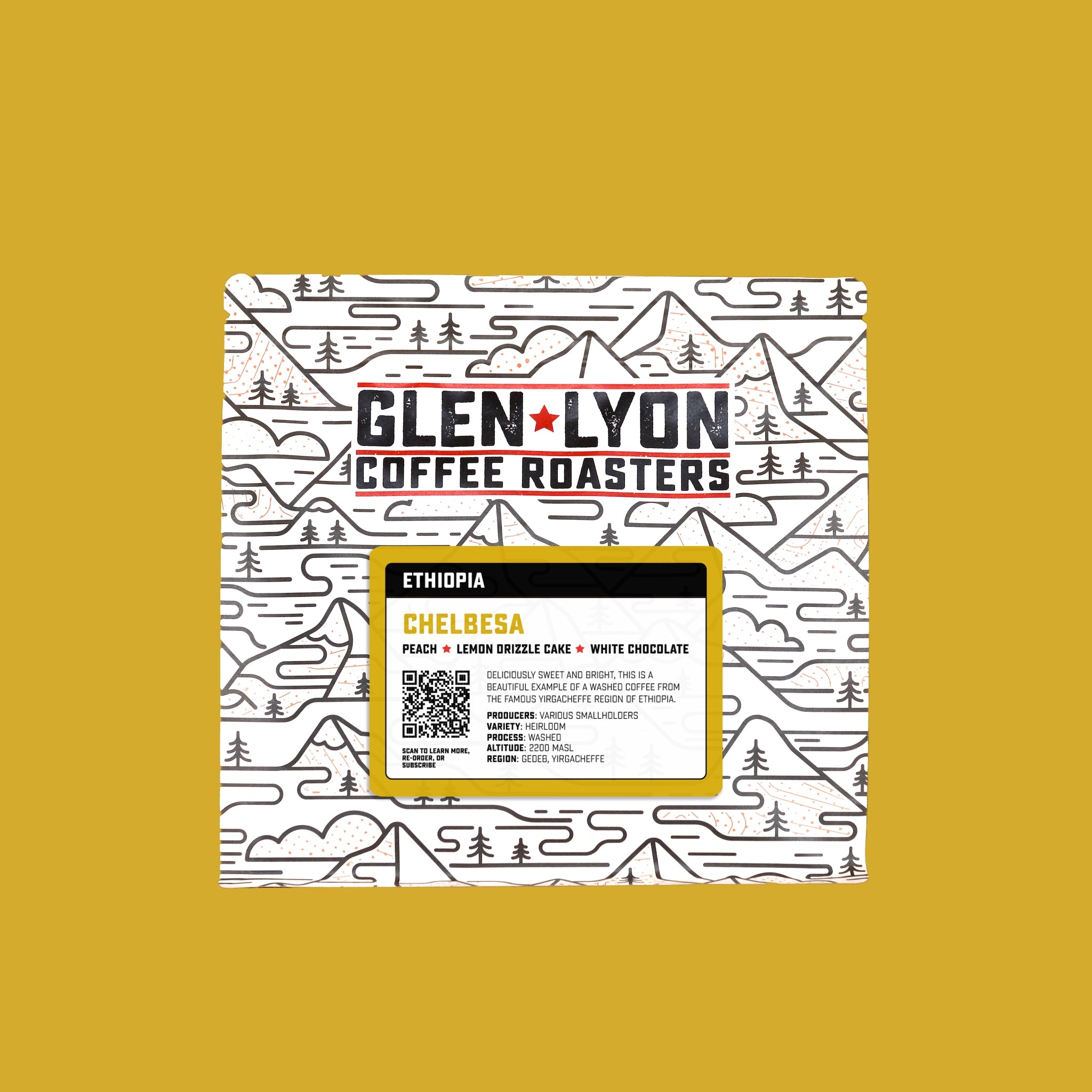

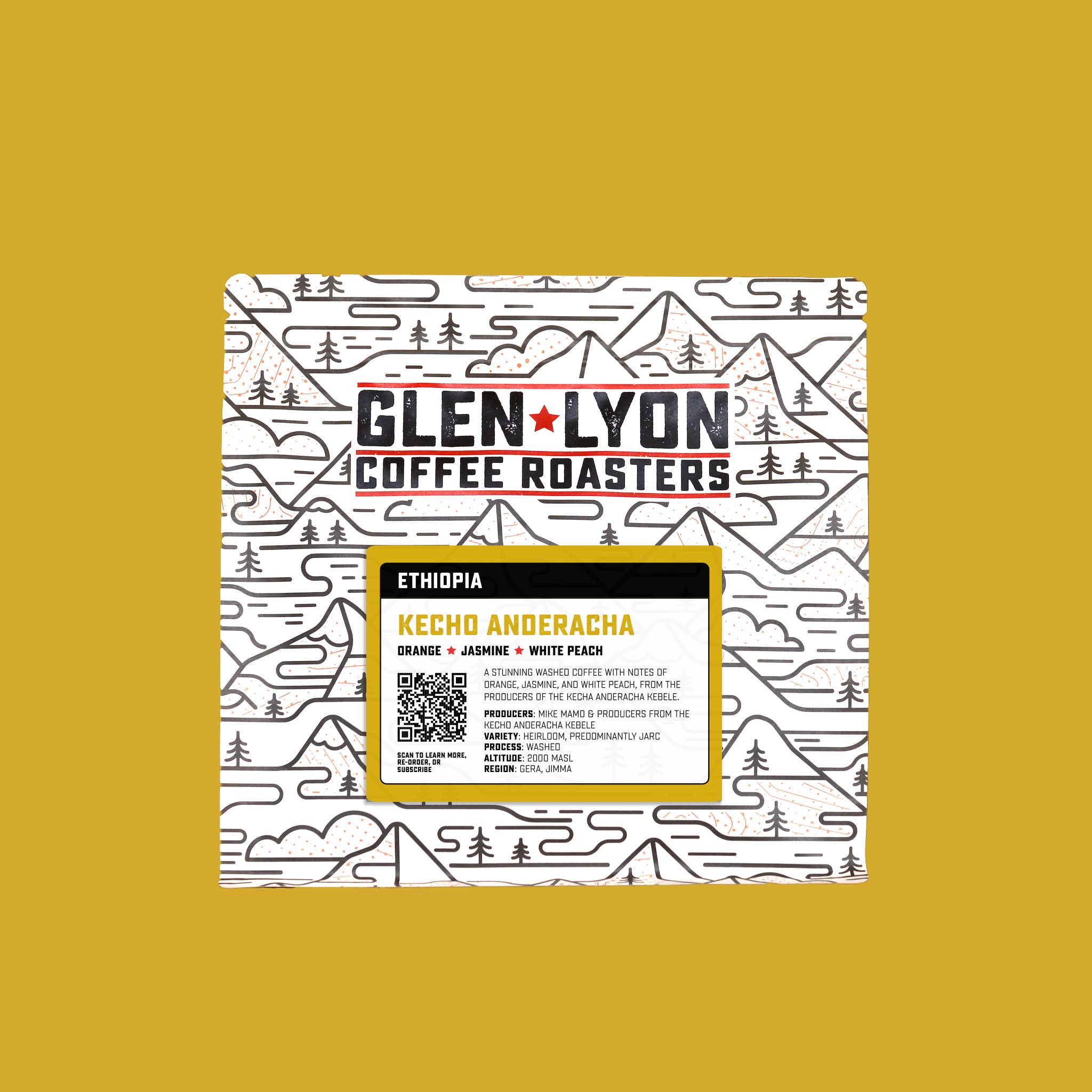

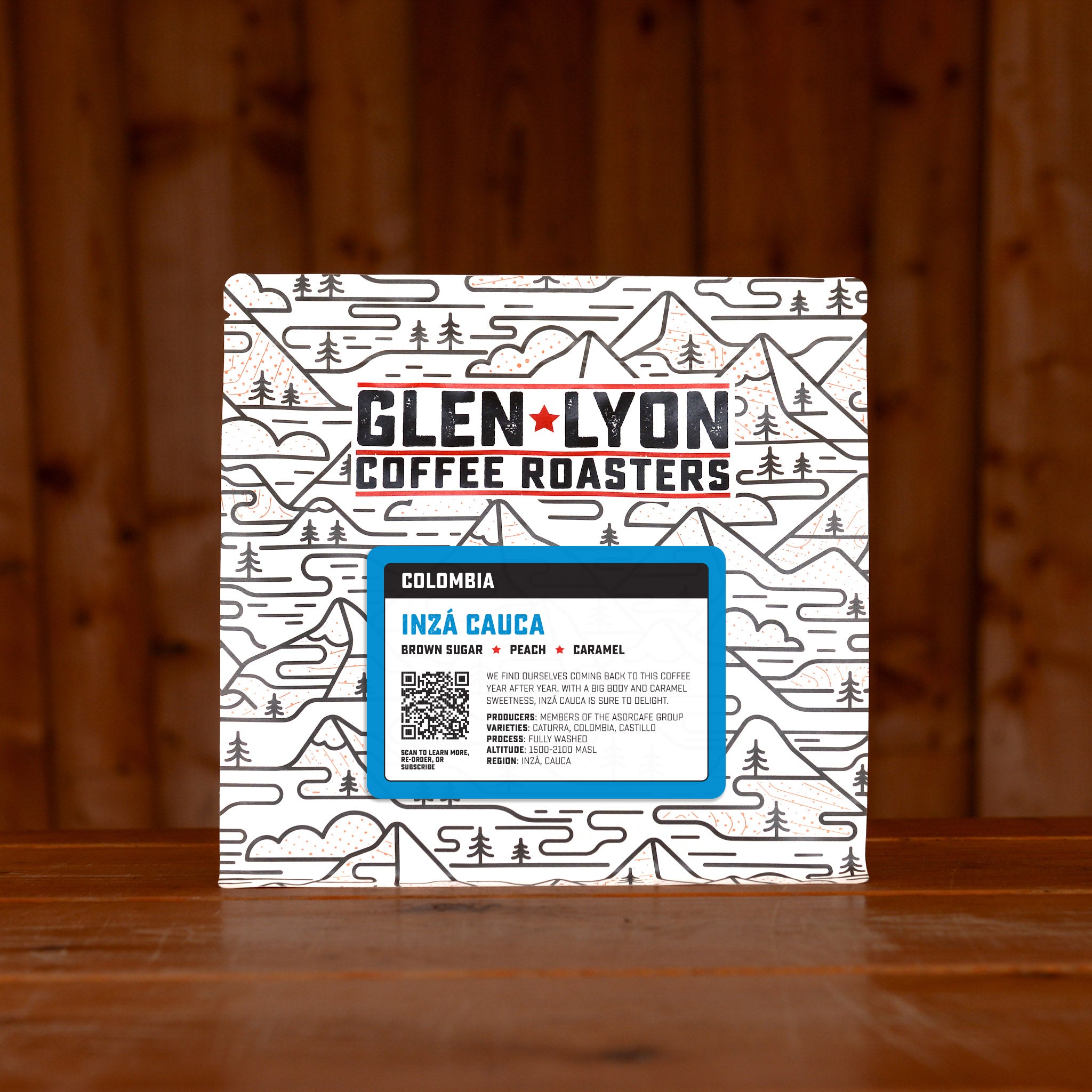

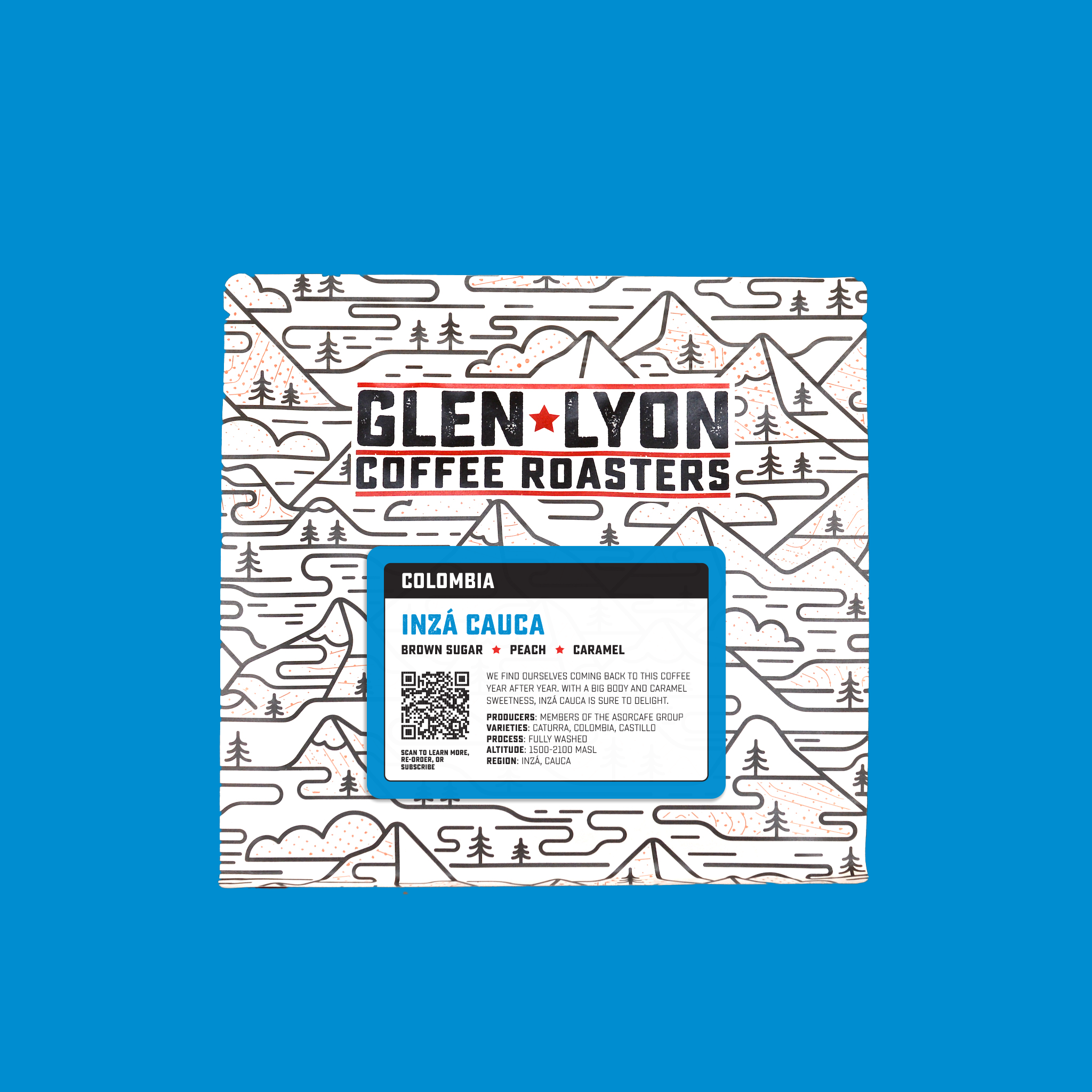

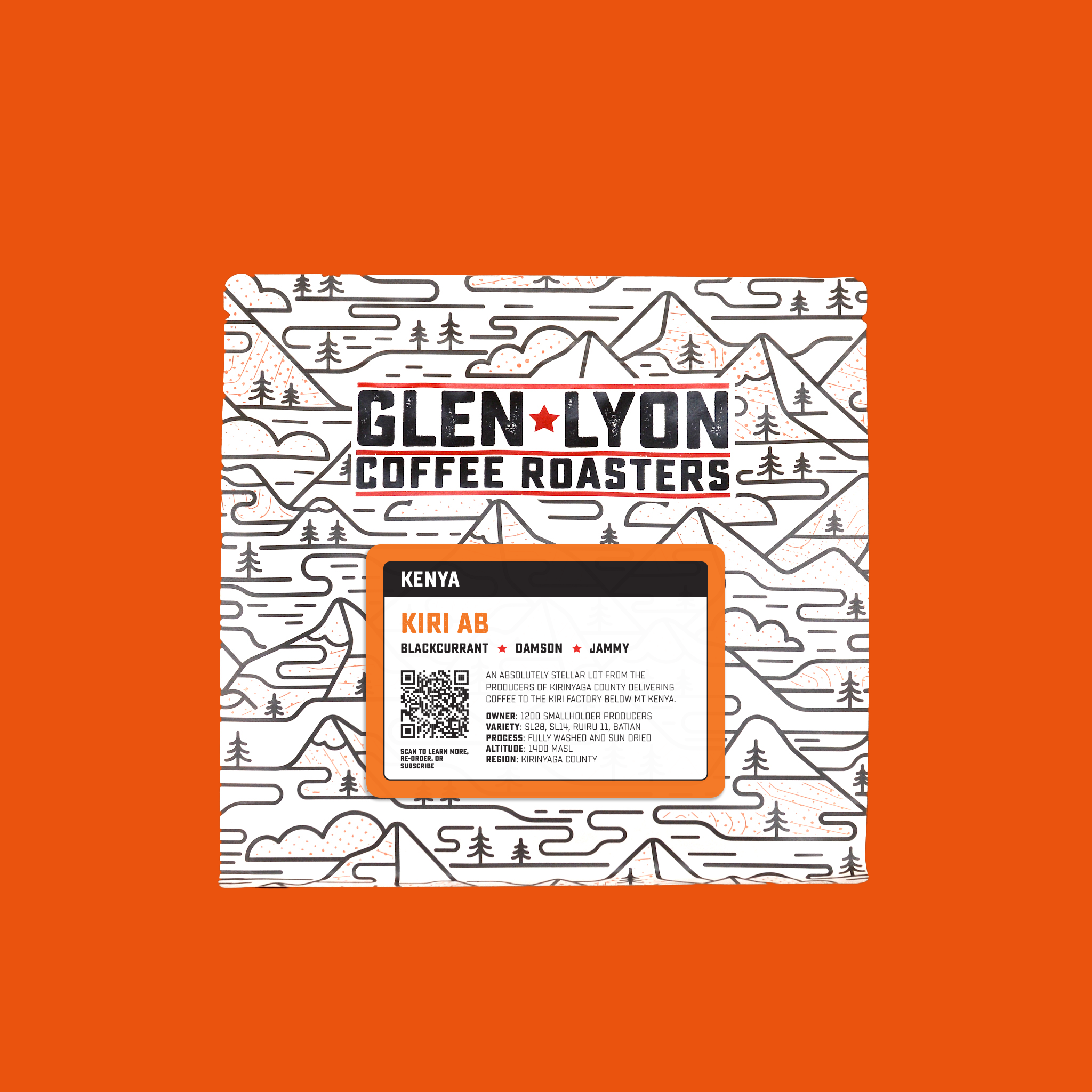

Washed process

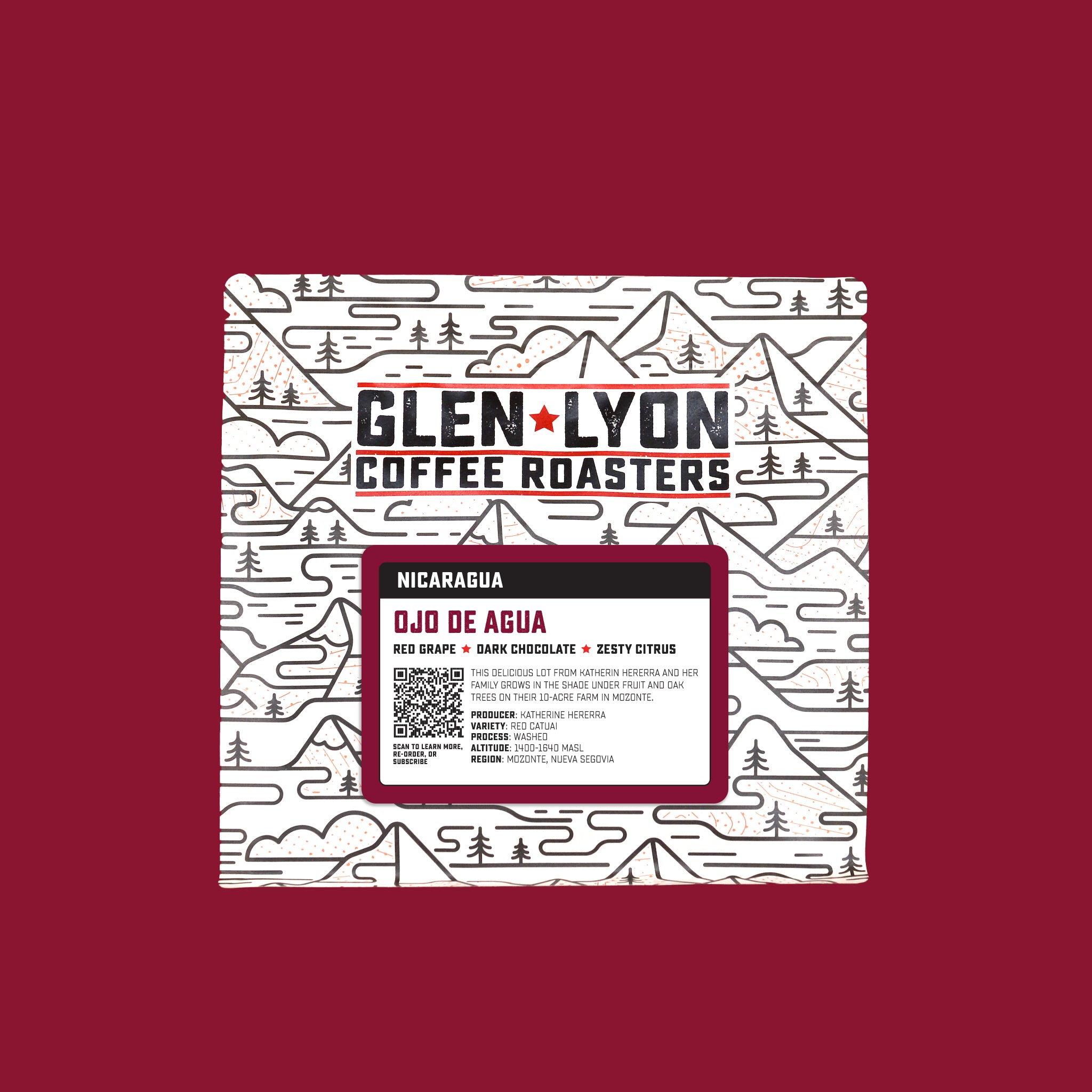

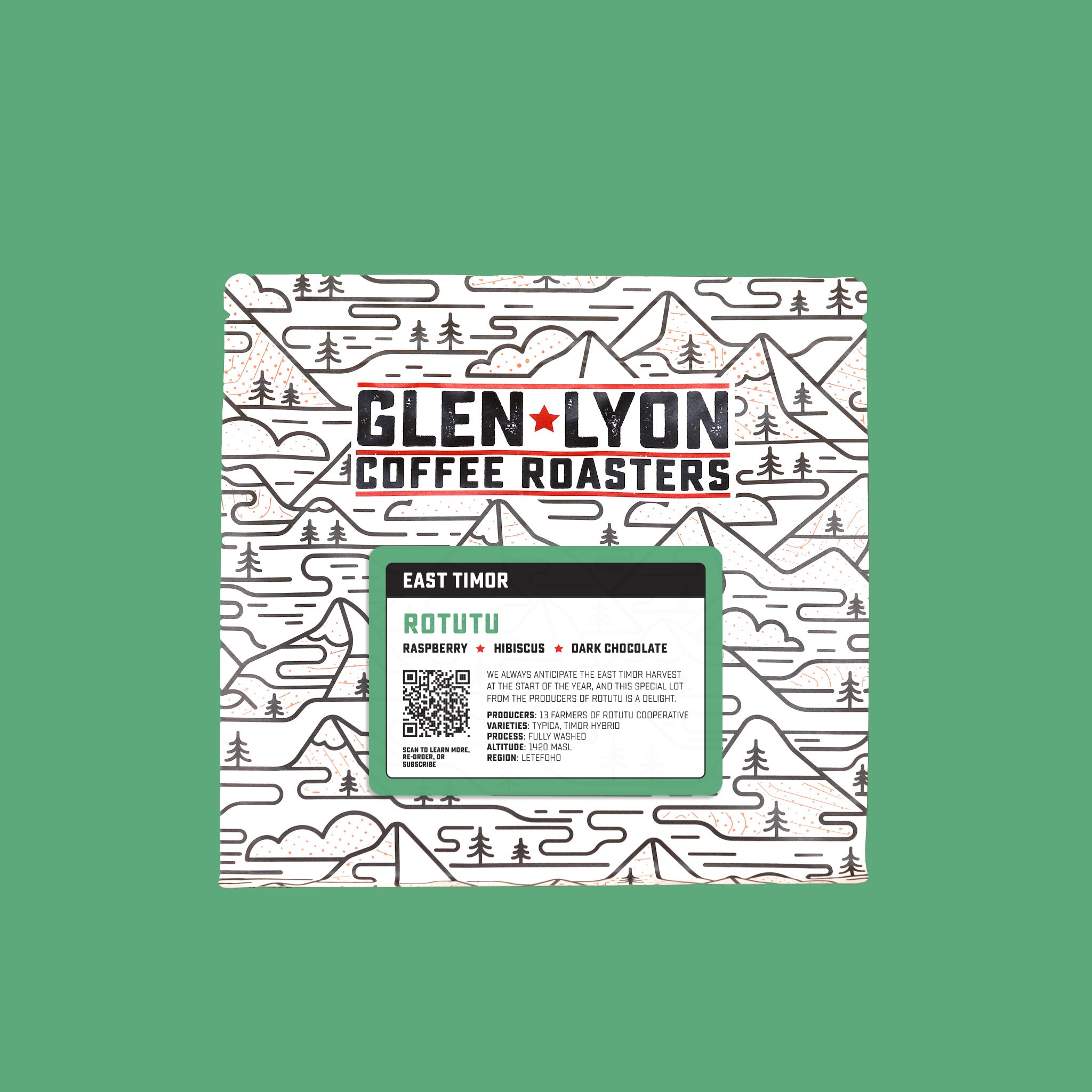

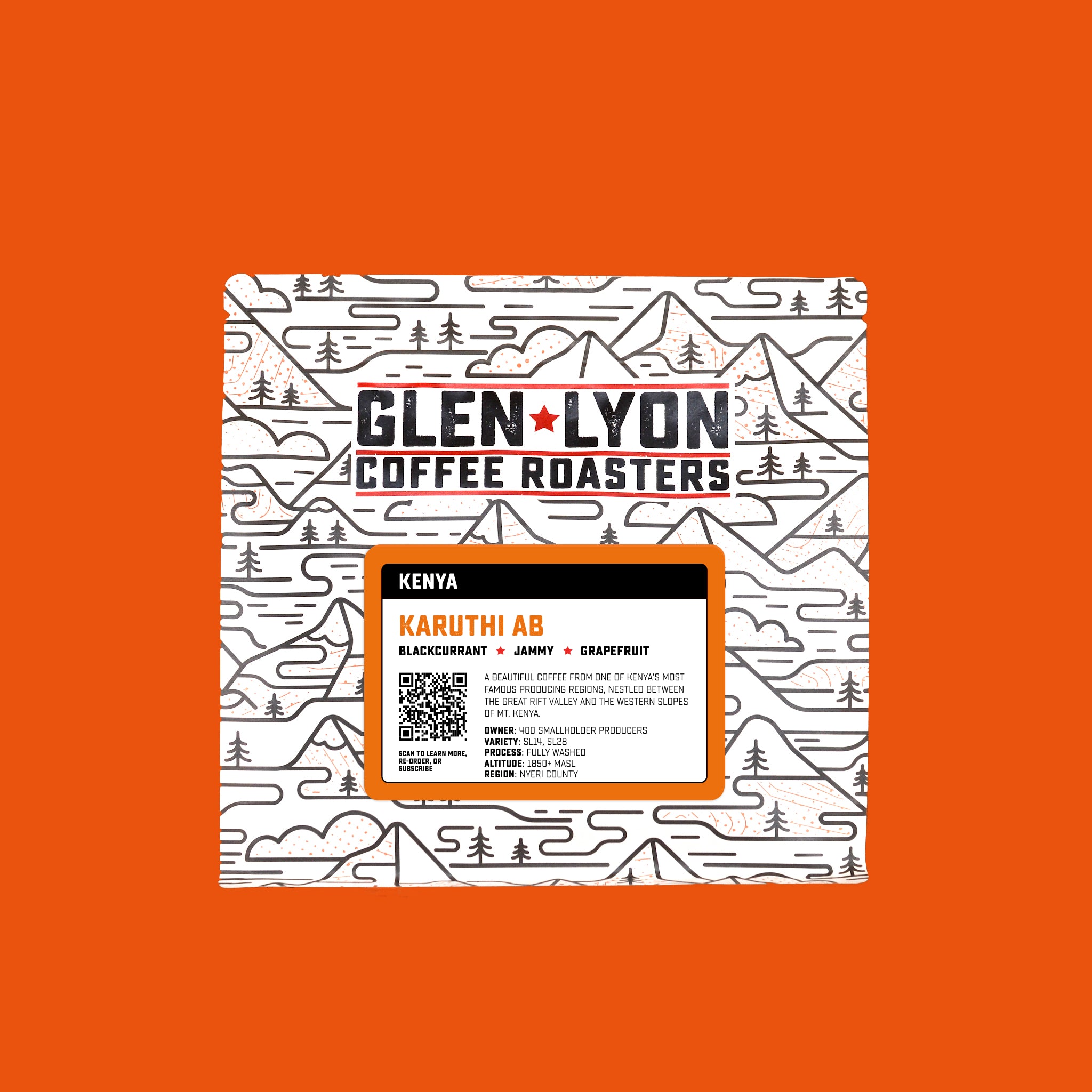

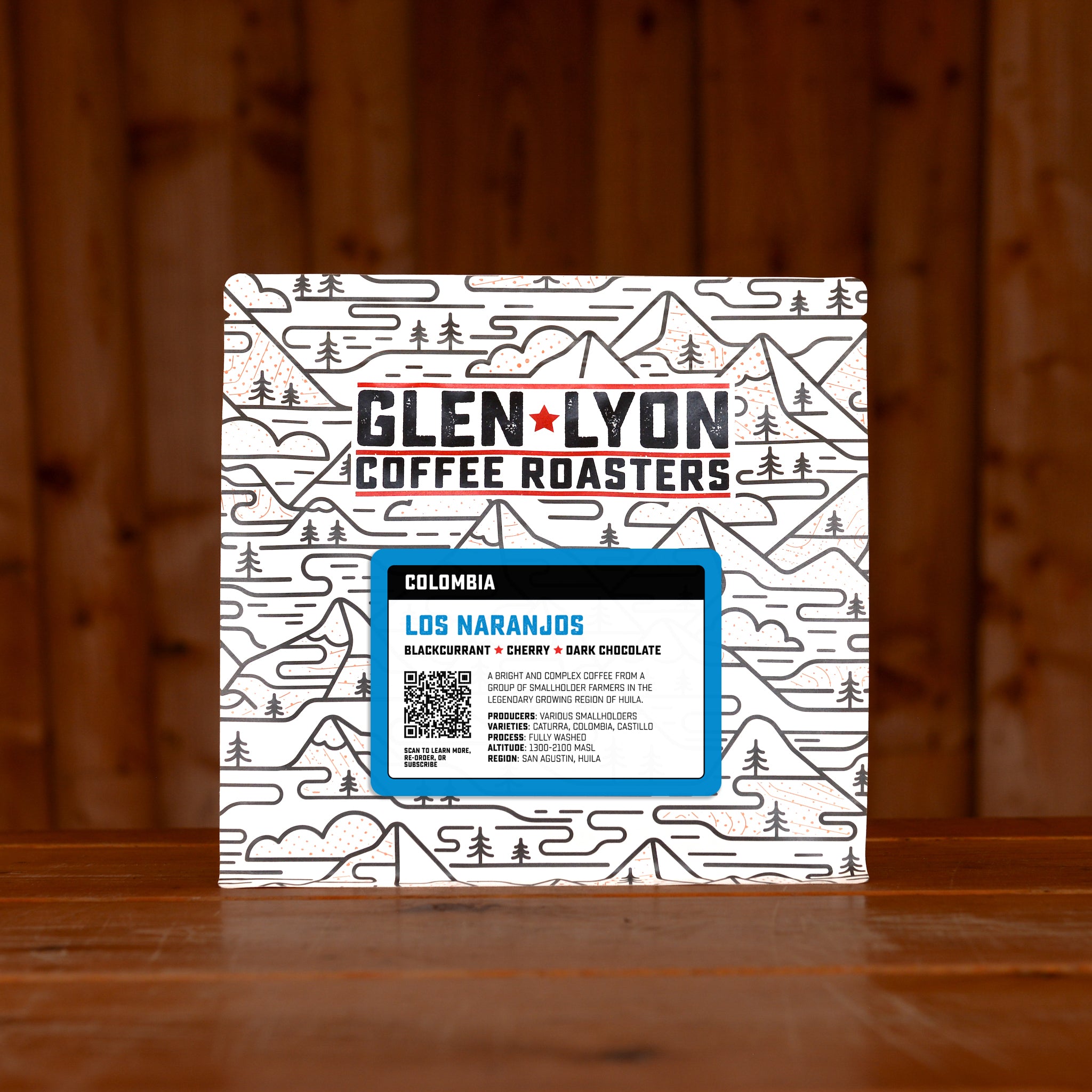

The most popular method worldwide, washed (or wet) processing involves removing the entire cherry before the drying phase.

Cherries are picked and immediately taken to the wet mill (or washing station or factory, depending on where in the world you are). This can be a simple setup on a farmer’s land or a huge centralised facility that processes coffee from hundreds of producers. Within 24 hours of picking the cherries are sorted, either by hand or in water-filled tanks where any unripe beans will float to the surface.

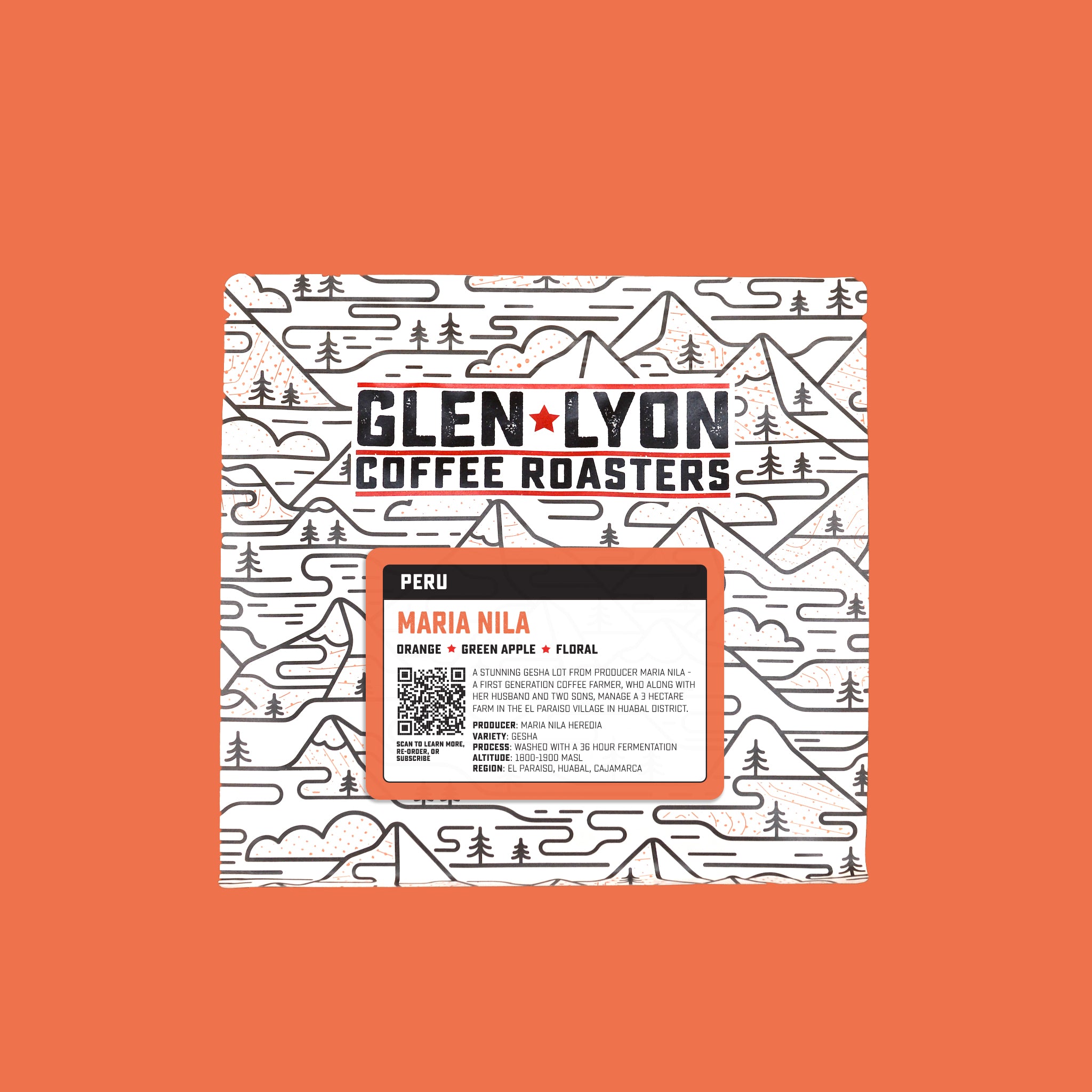

Next comes the depulping stage, which involves passing freshly-picked cherries through a machine somewhat similar to a mangle which removes the pulp and skin. What’s left—the bean and its sticky mucilage—is then put into big tanks to ferment for up to 72 hours. During this time the mucilage breaks down to the point where the beans can be washed a final time to remove the last remnants before drying, either in the sun, on patios or raised beds, or in mechanical dryers.

The time, specific techniques and equipment used during this processing can all impact the taste of the final coffee. In general washed coffees will taste cleaner and are sometimes thought to be a “truer” expression of a coffee’s inherent flavours due to the lack of influence from the fruit of the cherry (although this is up for debate).

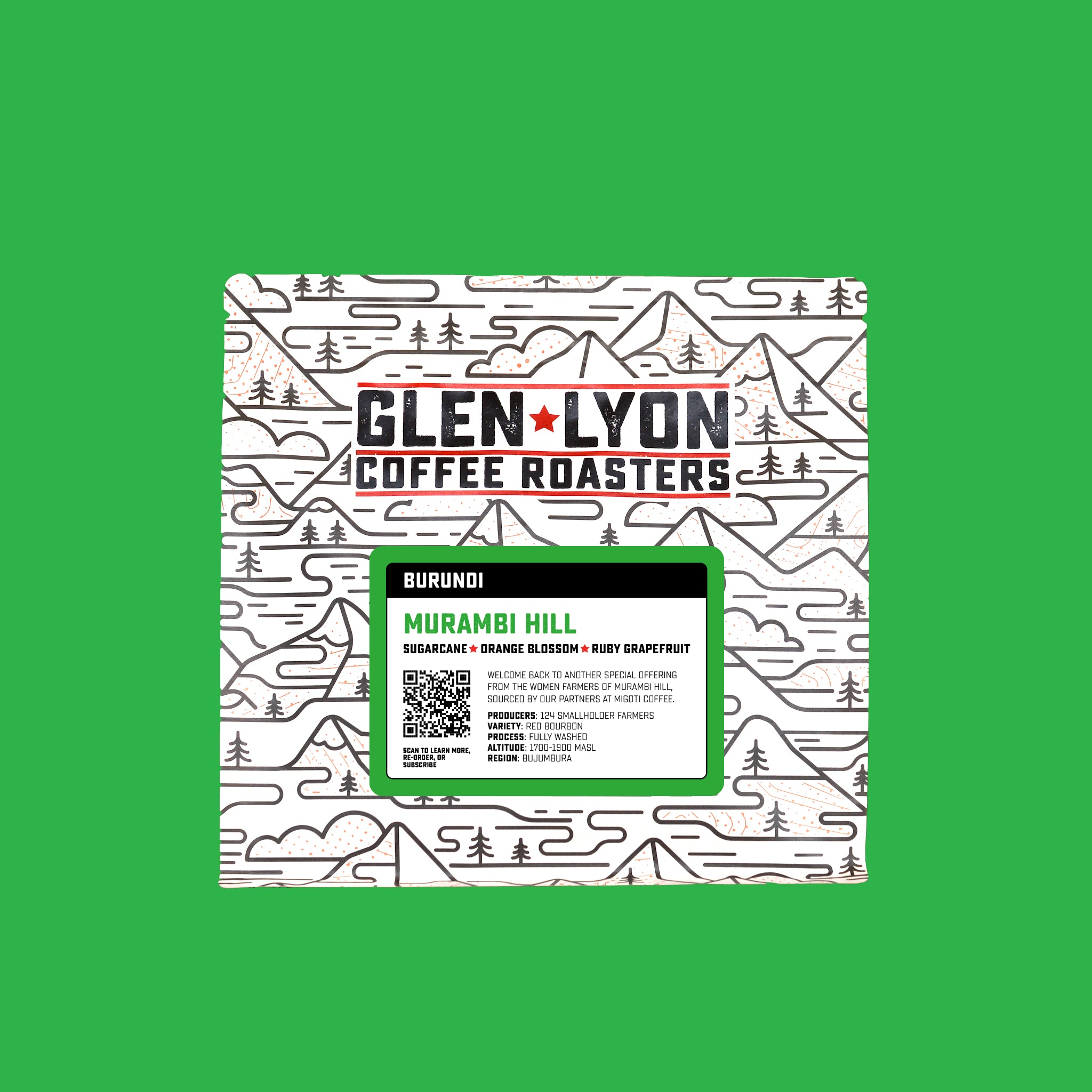

The washed process allows for a level of consistency that natural coffees often lack, and is sought-after by specialty roasters for the clarity and brightness of its final product. It is however a more expensive method, and obviously uses much more water than the natural process, so is not always a viable prospect for producers in certain countries.

It is also sometimes considered less environmentally friendly than the natural process due to the amount of water used and the possibility of contamination from wastewater discharge. However the washed process is most often used in places that receive a lot of rainfall, and farmers are constantly innovating new techniques to use less water and reuse what they do utilise as fertiliser.

PULPED NATURAL / SEMI-WASHED / HONEY

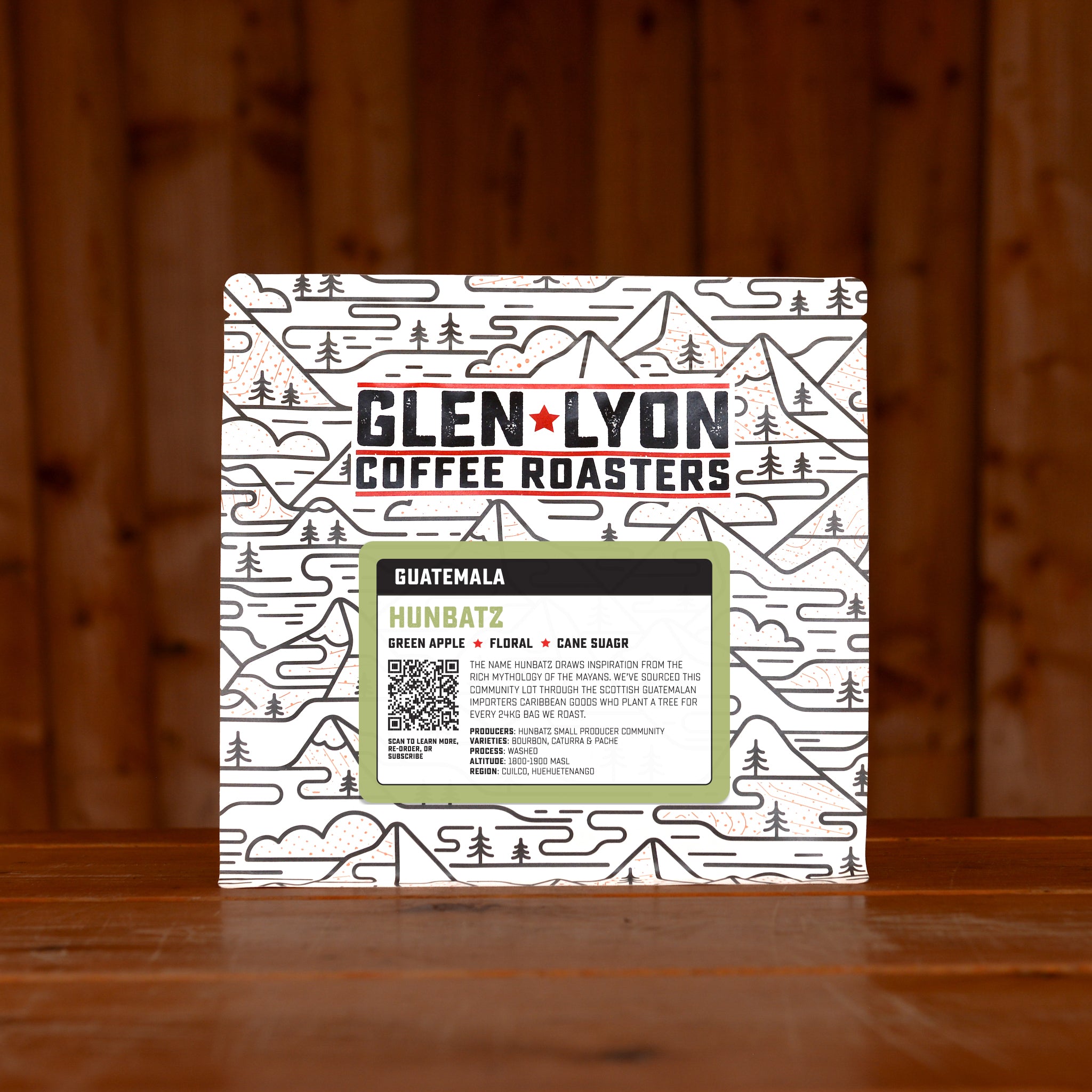

The washed and natural methods are the two most popular coffee processing techniques worldwide, but in between these two polarities exists a range of methods that blur the lines between them.

Their names might differ depending on the location and specifics of the method, but in general these techniques aim to combine the best aspects of the washed and natural processes: the depth, complexity and sweetness of the best naturals with the clarity and, importantly, efficiency of the washed process.

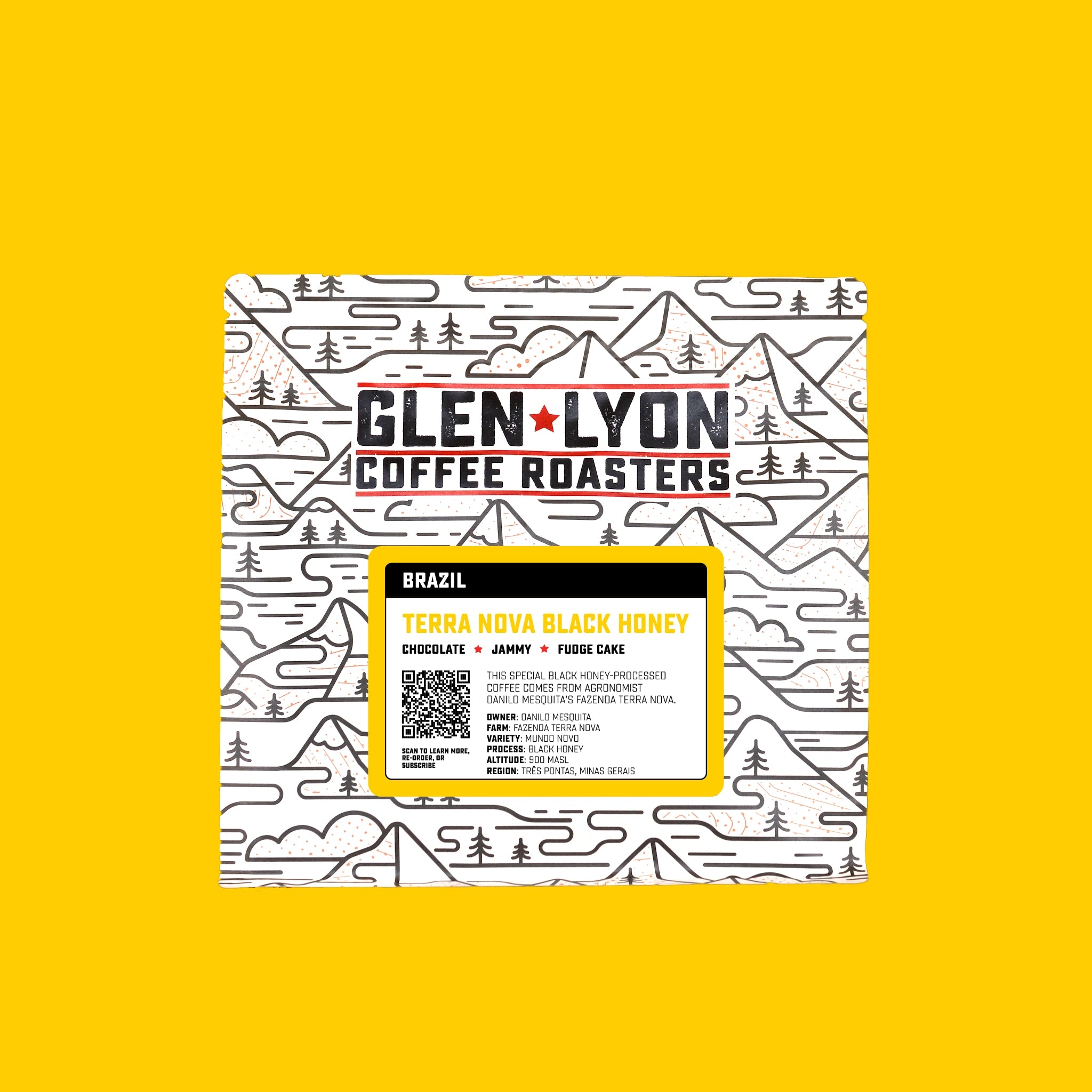

Pulped natural and semi-washed are two names for essentially the same method. Pulped natural originated in Brazil in the early 21st century as a way to speed up the drying process (natural coffees can take upwards of six weeks to fully dry). Similar to the washed method, the coffee is picked and then depulped to remove the skin but some of the sticky mucilage is left on the beans which are then laid out to dry.

After drying to the desired moisture content, the beans are further processed to remove the remaining mucilage and parchment before being readied for export.

What about honey?

The honey process (which doesn’t involve any actual honey) is another term for pulped natural, most popular in Central American countries like Costa Rica and Guatemala. There are different names—White Honey, Red Honey, Black Honey—which refer to the amount of mucilage left on the beans as they dry and their subsequent colour. White Honey coffees have the least amount of pulp and are closer to a fully-washed coffee, whereas Black Honey coffees are closer to naturals in look and taste.

To complicate things further, countries like Indonesia have their own specific versions of the semi-washed method. Indonesia’s Giling Basah is a fascinating process, so if you’re interested this article from Sweet Maria’s delves deep.

A NOTE ON FERMENTATION

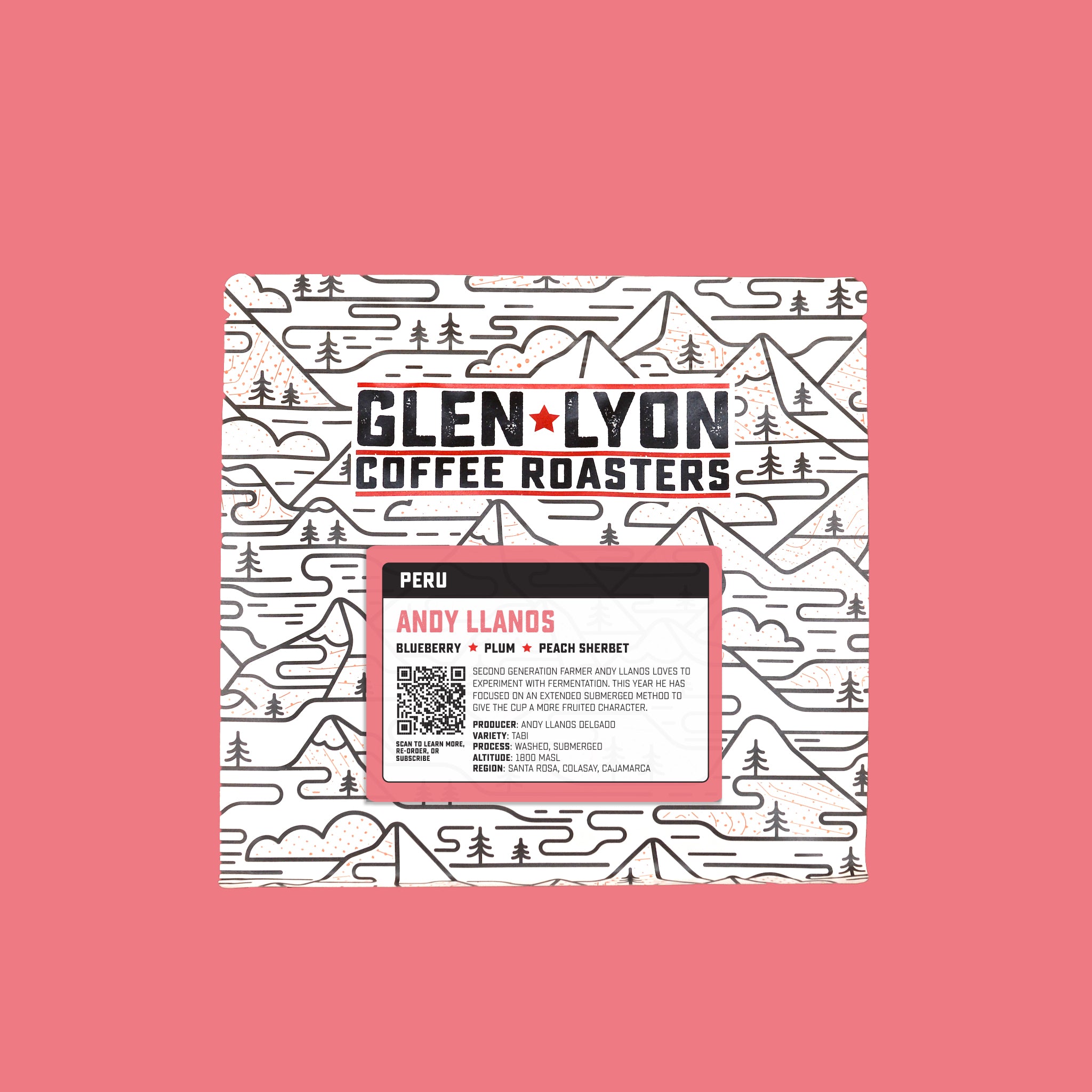

You might have seen the words “extended fermentation” or “anaerobic fermentation” on some of our coffees recently, so we thought it might be a good idea to talk a little bit about what this means. These extra fermentation techniques were adapted from the winemaking world, and have become very popular in coffee as a way to enhance flavours and help specific lots stand out.

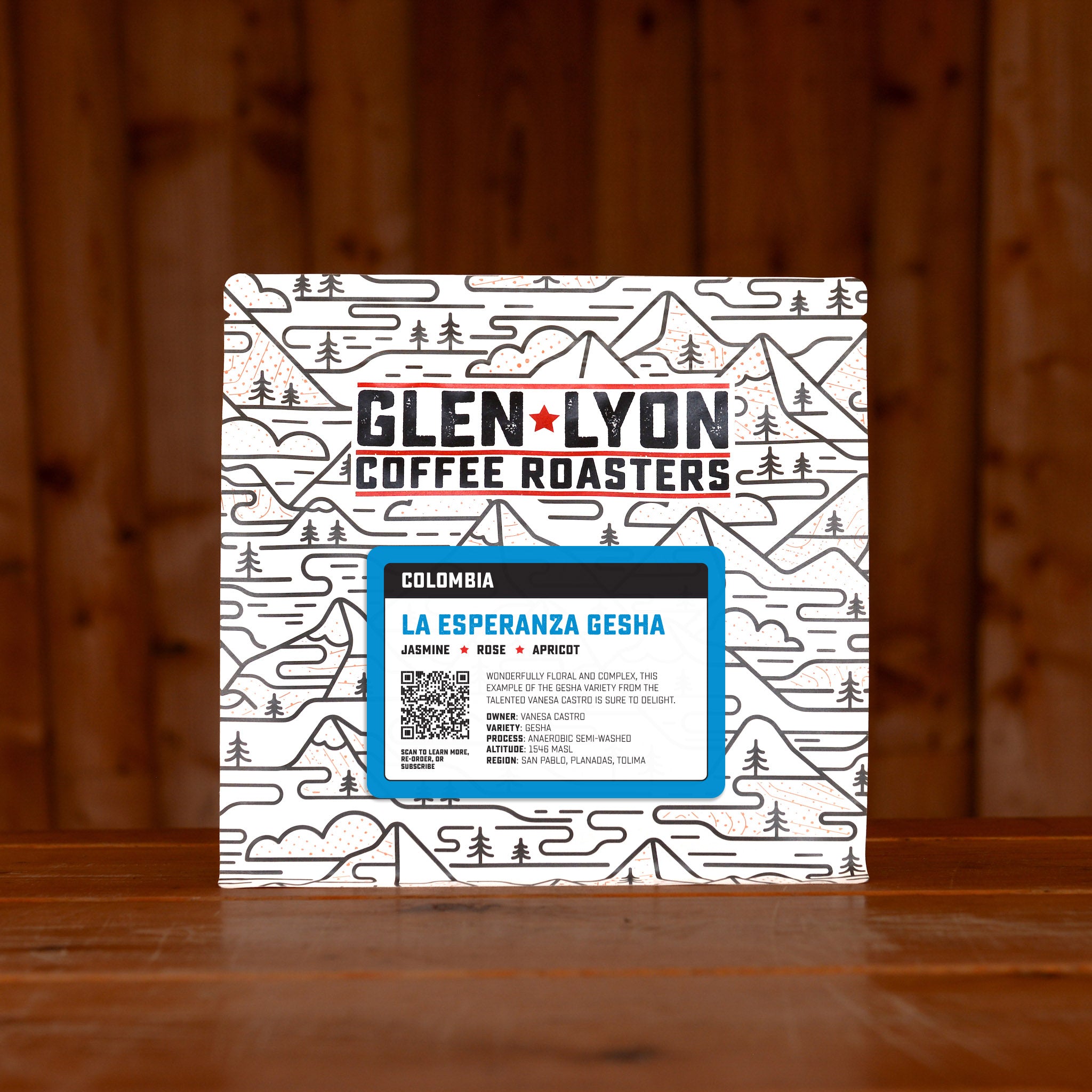

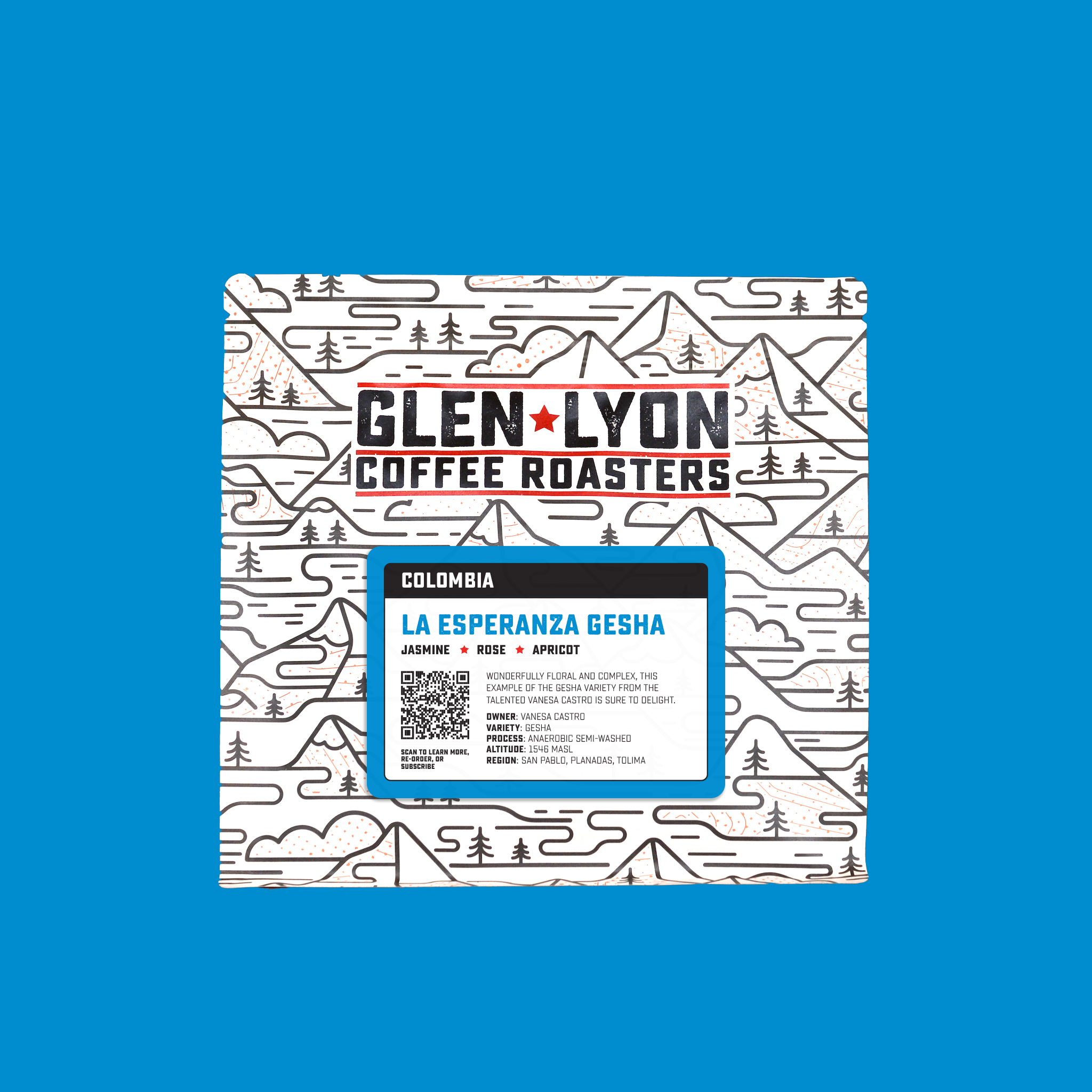

All coffee ferments during the processing period—fermentation begins as soon as the cherry is picked—but producers actively encouraging, prolonging, and controlling the process is a relatively recent phenomenon. Fermentation is the process by which microorganisms like yeasts and bacteria break down sugars in the mucilage to create a coffee’s acidity and fruit notes. Manipulating this process—removing oxygen, or extending the fermentation—can give the final cup noticeably different and unique flavours, and can be applied during washed, natural, or honey processing.

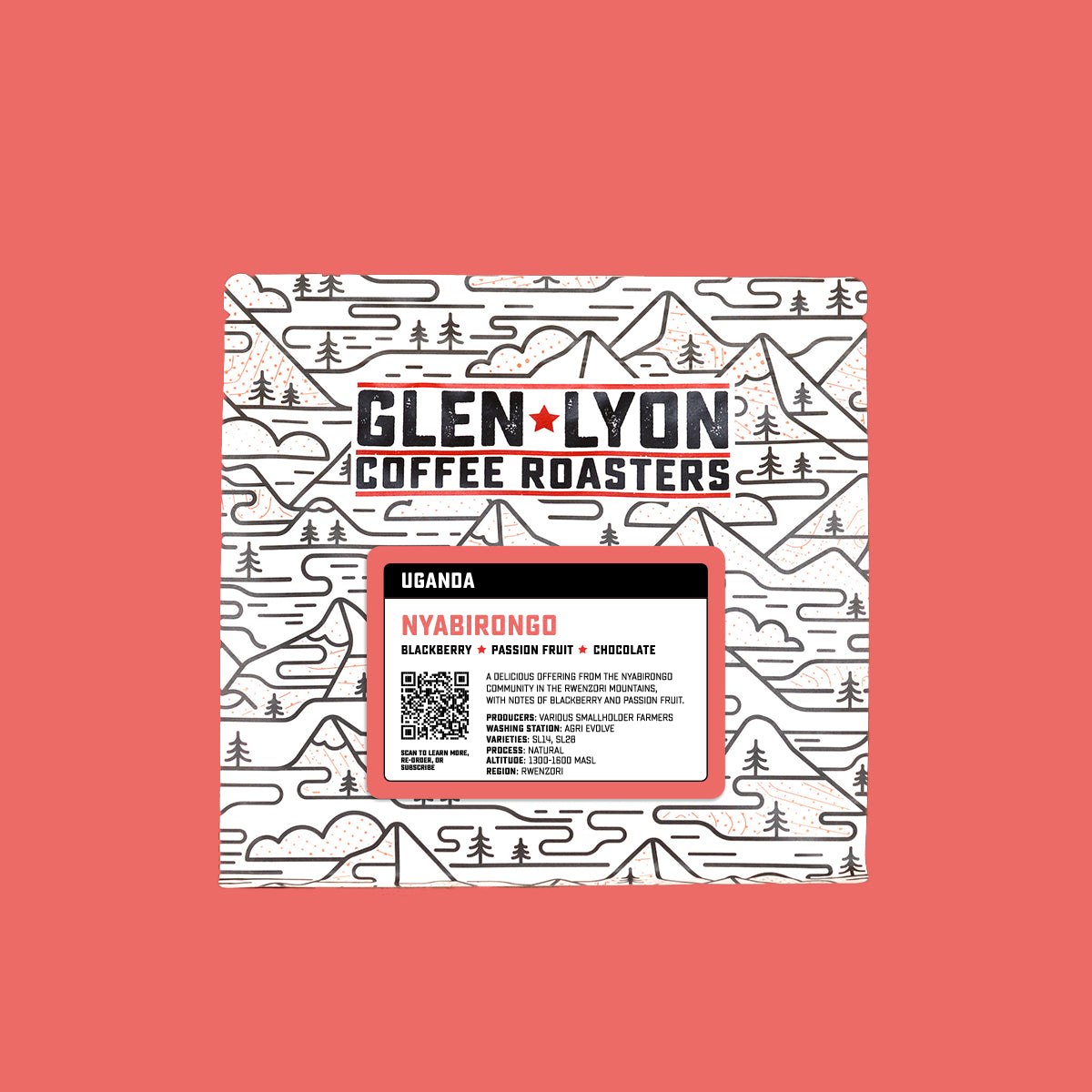

Anaerobic fermentation is one of the most popular of these experimental methods. The farmer seals the freshly-harvested and depulped cherries in an oxygen-deprived chamber like a bag, barrel or vat, for a specific period of time. Oxygen is forced out through a one-way valve or sometimes by introducing CO2 (what’s known as carbonic maceration). After the specified time has passed the coffee is removed and the processing continues in the ways outlined above.

Coffees processed in this way will sometimes be noticeably fruitier or accentuate the coffee’s already-present flavours. Be prepared for an experience!