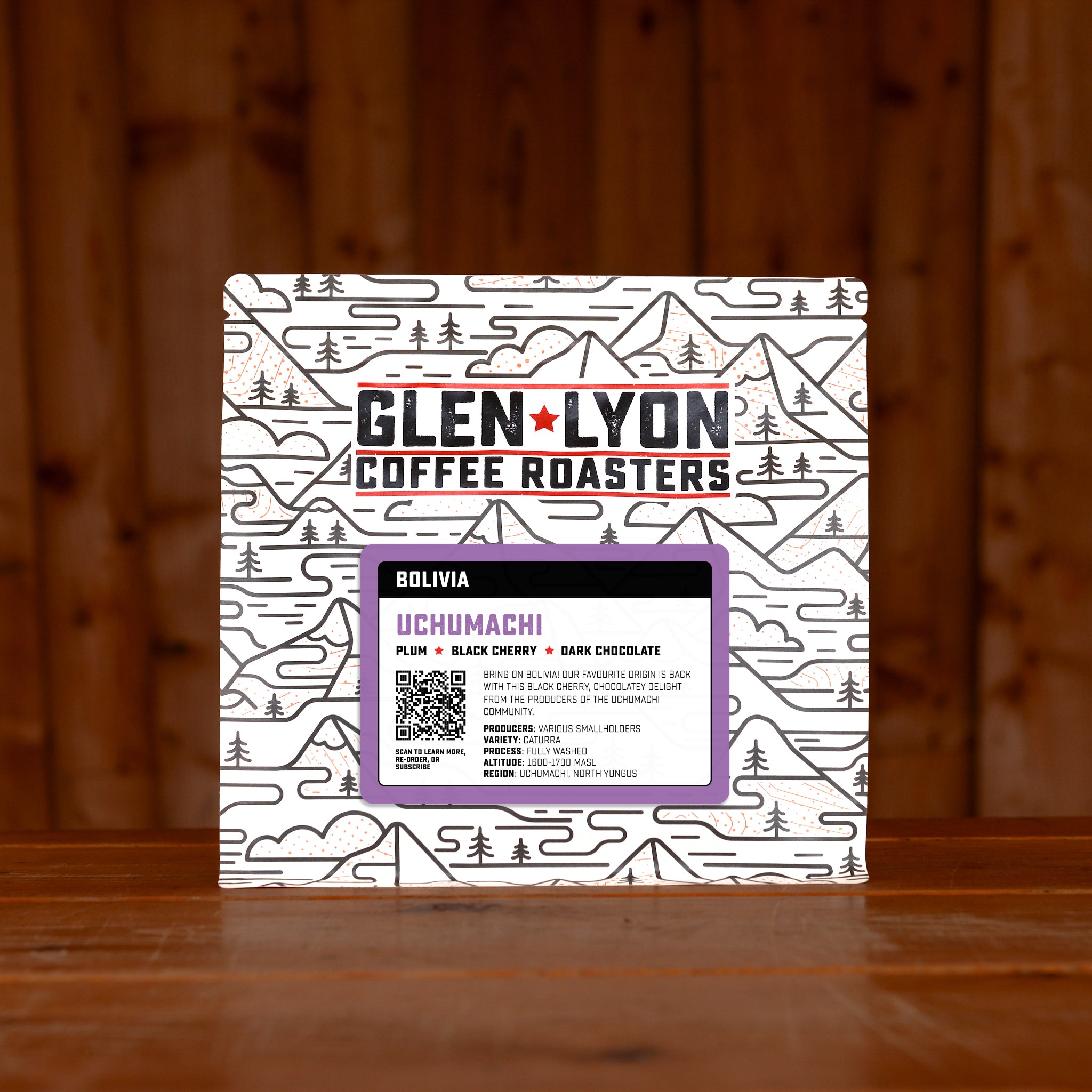

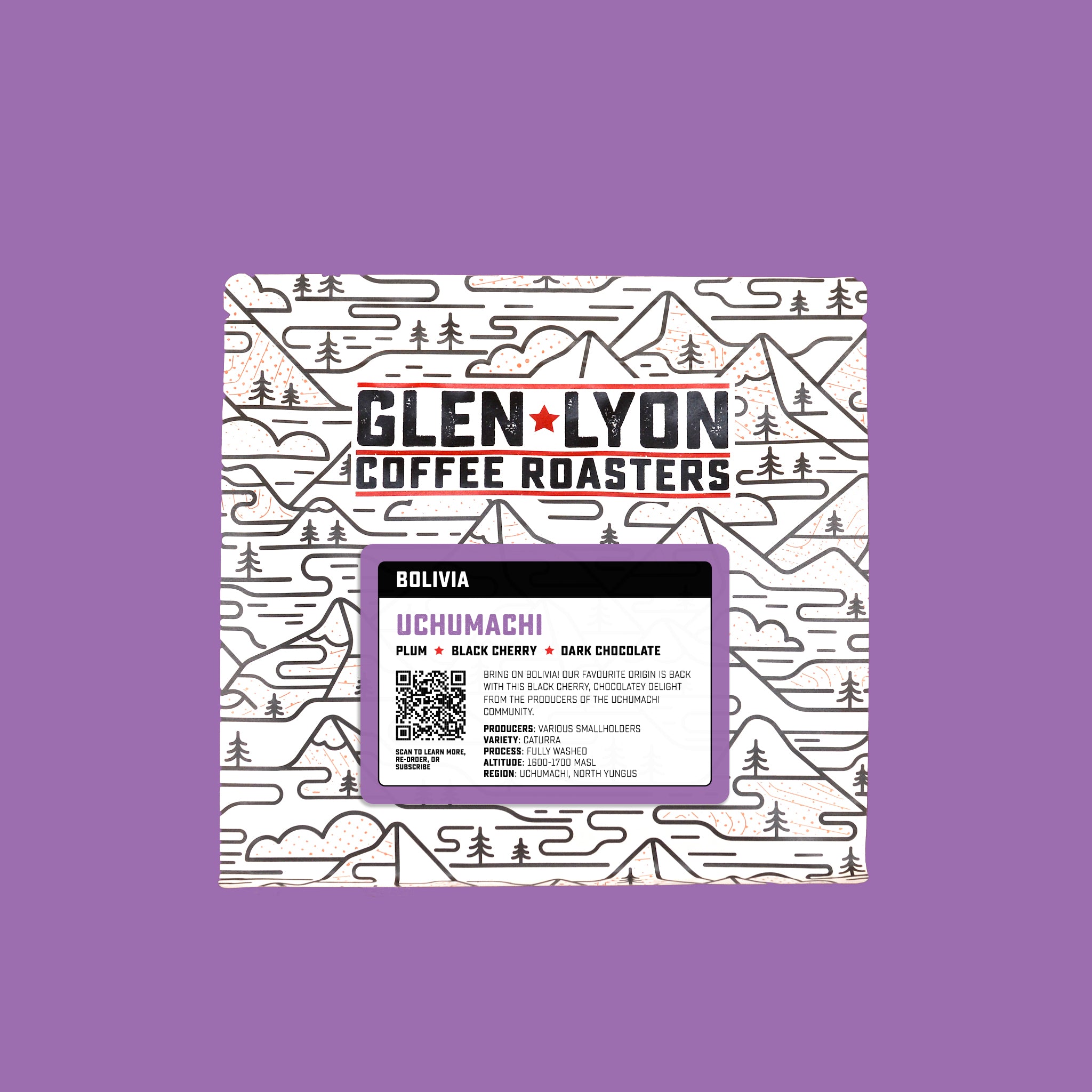

Another year, another delivery of this very special coffee from the famous coffee producing Mamani family of Bolivia’s remote Uchumachi community high in the Bolivian Yungas.

The Yungas is a hugely biodiverse ecoregion that stretches along the eastern slope of the Andes mountain range from Peru to Bolivia and into Argentina. In Bolivia, the region ranges from 400 up to 3,500 metres and is made up of a combination of tropical rainforest and cloud forests. Northern trade winds deposit fog and rain across the high mountains and provide a suitably warm, humid environment for growing coffee.

The Bolivian Yungas has always been central to the country’s coffee production, with one report from 1902 noting that the plant was so well-suited to the region that merely dropping a seed on the ground resulted in a plant. However, because of the region’s remoteness and poor infrastructure, coffee production has always been relatively low.

Prior to the 1952 Bolivian National Revolution, the vast majority of the country's cultivable land was owned by huge estates of 1,000 acres or more. Following the revolution, land reform laws expropriated and redistributed low-productivity rural property to the country’s mainly indigenous labourers.

This led to an influx of young farmers to the Yungas, and saw coffee production increase—albeit haphazardly, because most of the migrants had no experience farming and were largely left to figure things out on their own. The creation of cooperatives and growers associations helped to improve yields and incomes, and Bolivia’s production peaked in the 1990s.

Over the past few decades, Bolivia’s coffee production has been in steady decline and today remains relatively low—as of 2022, it was the world’s 39th largest exporter, behind countries like Cuba and Togo. This is due in part to old trees, which produce fewer cherries as they age, as well as competition from crops like coca.

Coca carries great cultural, ceremonial, and medicinal importance to the people of the Andean altiplano, and its production is legal in the Yungas. Coca is much easier to cultivate and more lucrative for small farmers, but successive Bolivian (and United States) governments have attempted to incentivise farmers to swap their coca crops for coffee.

At the same time, efforts such as those by our export partners Agricafe, which provides education and training in best agricultural practices to help farmers improve both quality and yield, are beginning to put Bolivia back on the coffee map. And it’s not just production that is increasing—Bolivia’s coffee scene has exploded in recent years, with La Paz and other bigger cities seeing a growth in speciality cafes as local consumption has increased.However the country’s landlocked status and underdeveloped infrastructure means exporting coffee from Bolivia is a tricky task. In order to reach Scotland from Uchumachi, coffee has to first navigate treacherous terrain—including the fabled La Paz-Coroico road, also known as “el camino de la muerte” or “the road of death”.

René Mamani, who is originally from Escoma, got into coffee when he was a teenager and used to visit his brother-in-law Mauricio Mamani in Uchumachi and help him on the farm. In 2009 René took the leap and bought a 14-hectare plot with his brother Juan and has been growing coffee independently ever since. When René's not working he enjoys relaxing, enjoying the beautiful countryside in that region and taking his daughters to swim in the river and the natural pools.

René Mamani, who is originally from Escoma, got into coffee when he was a teenager and used to visit his brother-in-law Mauricio Mamani in Uchumachi and help him on the farm. In 2009 René took the leap and bought a 14-hectare plot with his brother Juan and has been growing coffee independently ever since. When René's not working he enjoys relaxing, enjoying the beautiful countryside in that region and taking his daughters to swim in the river and the natural pools.

The best part about growing coffee in René's opinion is working with the nursery and the coffee in its first year. "They're like my babies," he says. "That's why I want to plant another hectare. He delights in watching the plants grow and seeing the amount of cherries they're producing. And that makes him happy, thinking about their production and the income it means for his family. René's extended family has coffee farms in the region and he enjoys what he calls "healthy competition" in their coffee growing. He says seeing his relatives set and meet their production goals helps keep him motivated as well."I can't fall asleep, I have to keep doing things well!'

This particular lot from Rene was produced by the 'washed mosto' process, a type of fermentation process in which the juicy mucilage (that would have been been removed during the depulping stage, is then added back into the fermentation tanks with the coffee in order to create a more complex fermentation.

We’ve been working with the Mamani Family and other producers of Uchumachi for years now—the first pallet of coffee Glen Lyon ever roasted came from the region—and we’re always excited to welcome Bolivian coffee into the roastery. It’s an honour to work with these producers and we hope you enjoy their coffee as much as we do.